https://press.asimov.com/articles/dna-information

This is an article that just appeared in Asimov Press, who kindly agreed that I could publish it here and also humored my deep emotional need to use words like “Sparklepuff”.

Do you like information theory? Do you like molecular biology? Do you like the idea of smashing them together and seeing what happens? If so, then here’s a question: How much information is in your DNA?

When I first looked into this question, I thought it was simple:

-

Human DNA has about 3.1 billion base pairs.

-

Each base pair can take one of four values (A, T, C, or G)

-

It takes 2 bits to encode one of four possible values (00, 01, 10, or 11)

-

Thus, human DNA contains 6.2 billion bits.

Easy, right? Sure, except:

-

You have two versions of each base pair, one from each of your parents. Should you count both?

-

All humans have almost identical DNA. Does that matter?

-

DNA can be compressed. Should you look at the compressed representation?

-

It’s not clear how much of our DNA actually does something useful. The insides of your cells are a convulsing pandemonium of interacting “hacks”, designed to keep working even as mutations constantly screw around with the DNA itself. Should we only count the “useful” parts?

Such questions quickly run into the limits of knowledge for both biology and computer science. To answer them, we need to figure out what exactly we mean by “information” and how that’s related to what’s happening inside cells. In attempting that, I will lead you through a frantic tour of information theory and molecular biology. We’ll meet some strange characters, including genomic compression algorithms based on deep learning, retrotransposons, and Kolmogorov complexity.

Ultimately, I’ll argue that the intuitive idea of information in a genome is best captured by a new definition of a “bit”—one that’s unknowable with our current level of scientific knowledge.

What is “information”? This isn’t just a pedantic question, as there are actually several different mathematical definitions of a “bit”. Often, the differences don’t matter, but for DNA, they turn out to matter a lot, so let’s start with the simplest.

In the storage space definition, a bit is a “slot” in which you can store one of two possible values. If some object can represent 2ⁿ possible patterns, then it contains n bits, regardless of which pattern actually happens to be stored.

So here’s a question we can answer precisely: How much information could your DNA store?

A few reminders: DNA is a polymer. It’s a long chain of chunks of ~40 atoms called “nucleotides”. There are four different chunks, commonly labeled A, T, C, and G. In humans, DNA comes in 23 pieces of different lengths, called “chromosomes”. Humans are “diploid”, meaning we have two versions of each chromosome. We get one from each of our parents, made by randomly weaving together sections from the two chromosomes they got from their parents.

At least, that's true for the first 22 chromosomes. For the last, females have two "X" chromosomes, while males have one "X" and one "Y" chromosome. There's no mixing between these, so men pass on one to their children pretty much unchanged1.

Chromosomes 1-22 have a total of 2.875 billion nucleotides; the X chromosome has 156 million, and the Y chromosome has 62 million. From here, we can calculate the total storage space in your DNA. Remember, each nucleotide has 4 options, corresponding to 2 bits. So if you’re female, your total storage space is:

(2×2875 + 2×156) million nucleotides

× 2 bits / nucleotide

= 12.12 billion bits

= 1.51 GB.

If you’re male, the total storage space is:

(2×2875 + 156 + 62) million nucleotides

× 2 bits / nucleotide

= 11.94 billion bits

= 1.49 GB.

For comparison, a standard single-layer DVD can store 37.6 billion bits or 4.7 GB. The code for your body, magnificent as it is, takes up as much space as around 40 minutes of standard definition video.

So in principle, your DNA could represent around 212,000,000,000 different patterns. But hold on. Given human common ancestry, the chromosome pair you got from your mother is almost identical to the one you got from your father. And even ignoring that, there are long sequences of nucleotides that are repeated over and over in your DNA, enough to make up a significant fraction of the total. It seems weird to count all this repeated stuff. So perhaps we want a more nuanced definition of “information.”

A string of 12 billion zeros is much longer than this article. But most people would (I hope) agree that this article contains more information than a string of 12 billion zeros. Why?

One of the fundamental ideas from information theory is to define information in terms of compression. Roughly speaking, the “information” in some string is the length of the shortest possible compressed representation of that string.

So how much can you compress DNA? Answers to this question are all over the place. Some people claim it can be compressed by more than 99 percent, while others claim the state of the art is only around 25 percent. This discrepancy is explained by different definitions of “compression”, which turn out to correspond to different notions of “information”.

If you pick any two random people on Earth, almost all of their DNA will be exactly the same. It's often said that people are 99.9 percent genetically identical, but this is wrong — it only measures substitutions and neglects things like insertions, deletions, and transpositions. If you account for all these things, the best estimate is that we are ~99.6 percent identical2.

The fact that we share so much DNA is key to how some algorithms can compress DNA by more than 99 percent. They do this by first storing a reference genome, which includes all the DNA that’s shared by all people and perhaps the most common variants for regions of DNA where people differ. Then, for each individual person, these algorithms only store the differences from the reference genome. Because that reference only has to be stored once, it isn’t counted in the compressed representation.

That’s great if you want to cram as many of your friends’ genomes on a hard drive as possible. But it’s a strange definition to use if you want to measure the “information content of DNA”. It implies that any genomic content that doesn’t change between individuals isn’t important enough to count as “information”. However, we know from evolutionary biology that it’s often the most crucial DNA that changes the least precisely because it’s so important. Heritability tends to be lower for genes more closely related to reproduction.

The best compression without a reference seems to be around 25 percent. (I expect this number to rise a bit over time, as the newest methods use deep learning and research is ongoing.) That’s not a lot of compression. However, these algorithms are benchmarked in terms of how well they compress a genome that includes only one copy of each chromosome. Since your two chromosomes are almost identical (at least, ignoring the Y chromosome), I’d guess that you could represent the other half almost for free, meaning a compression rate of around 50 percent + ½ × 25 percent ≈ 62 percent.

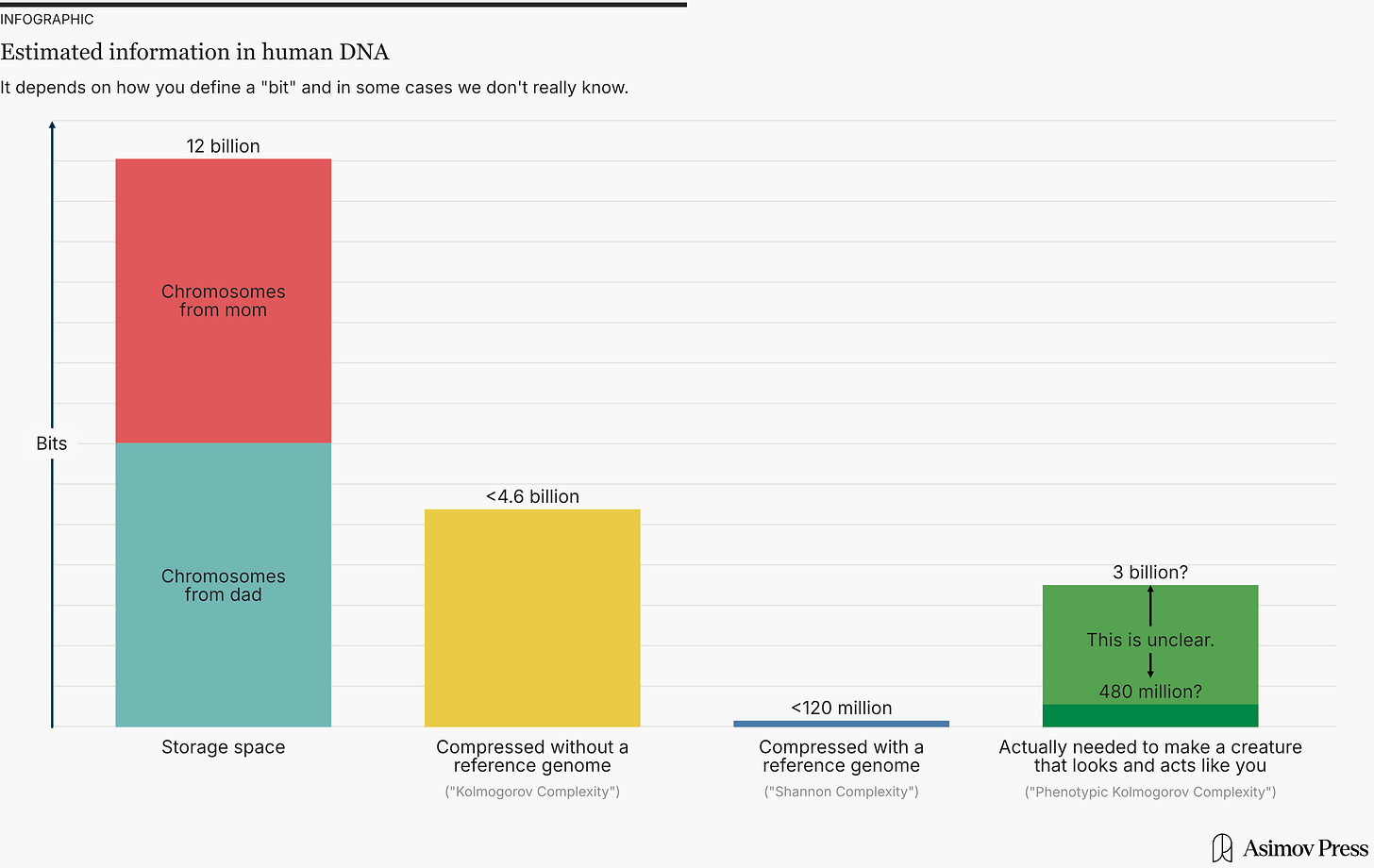

So if you compress DNA using an algorithm with a reference genome, it can be compressed by more than 99 percent, down to less than 120 million bits. But if you compress it without a reference genome, the best you can do is 62 percent, meaning 4.6 billion bits.

Which of these is right? The answer is that either could be right. There are two different definitions of a “bit” in information theory that correspond to different types of compression.

In the Kolmogorov complexity definition, named after the remarkable Soviet mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov, a bit is a property of a particular string of 1s and 0s. The number of bits of information in the string is the length of the shortest computer program that would output that string.

In the Shannon information definition, named after the also-remarkable American polymath Claude Shannon, a bit is again a property of a particular sequence of 1s and 0s, but it’s only defined relative to some large pool of possible sequences. In this definition, if a given sequence has a probability p of occurring, then it contains n bits for whatever value of n satisfies 2ⁿ=1/p. Or, equivalently, n=-log₂ p.

The Kolmogorov complexity definition is clearly related to compression. But what about Shannon’s?

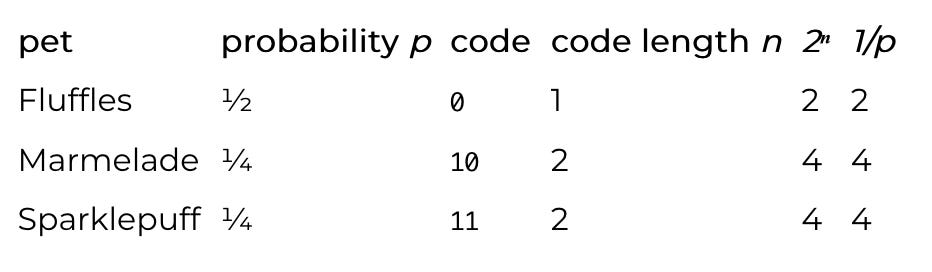

Well, say you have three beloved pet rabbits, Fluffles, Marmalade, and Sparklepuff. And say you have one picture of each of them, each 1 MB large when compressed. To keep me updated on how you’re feeling, you like to send me these same pictures over and over again, with different pets for different moods. You send a picture of Fluffles ½ the time, Marmalade ¼ of the time, and Sparklepuff ¼ of the time. (You only communicate in rabbit pictures, never with text or images.)

But then you decide to take off in a spacecraft, and your data rates go way up. Continuing the flow of pictures is crucial, so what’s the cheapest way to do that? The best thing would be that we agree that if you send me a 0, I should pull up the picture of Fluffles, while if you send 10 I should pull up Marmalade, and if you send 11, I should pull up Sparklepuff. This is unambiguous: If you send 0011100, that means Fluffles, then Fluffles again, then Sparklepuff, then Marmalade, then Fluffles one more time.

It all works out. The “code length” for Fluffles is the number n so that 2ⁿ=1/p:

Intuitively, the idea is that if you want to send as few bits as possible over time, then you should give short codes to high-probability patterns and long codes to low-probability patterns. If you do this optimally (in the sense that you’ll send the fewest bits over time), it turns out that the best thing is to code a pattern with probability p with about n bits, where 2ⁿ=p. (In general, things don’t work out quite this nicely, but you get the idea.)

In the Fluffles scenario, the Kolmogorov complexity definition would say that each of the images contains 1 MB of information since that’s the smallest each image can be compressed. But under the Shannon information definition, the Fluffles image contains 1 bit of information, and the Marmalade and Sparklepuff images contain 2 bits. This is quite a difference!

Now, let’s return to DNA. There, the Kolmogorov complexity definition basically corresponds to the best possible compression algorithm without a reference. As we saw above, the best-known current algorithm can compress by 62 percent. So, under the Kolmogorov complexity definition, DNA contains at most 12 billion × (1-0.62) ≈ 4.6 billion bits of information.

Meanwhile, under the Shannon information definition, you can assume that the distribution of all human genomes is known. The information in your DNA only includes the bits needed to reconstruct your genome. That’s essentially the same as compressing with a reference. So, under the Shannon information definition, your DNA contains less than 12 billion × (1-0.01) ≈ 120 million bits of information.

While neither of these is “wrong” for DNA, I prefer the Kolmogorov complexity definition for its ability to best capture DNA that codes for features and functions shared by all humans. After all, if you’re trying to measure how much “information” our DNA carries from our evolutionary history, surely you want to include that which has been universally preserved.

At some point, your high-school biology teacher probably told you (or will tell you) this story about how life works:

-

First, your DNA gets transcribed into matching RNA.

-

Next, that RNA gets translated into protein.

-

Then the protein does Protein Stuff.

If things were that simple, we could easily calculate the information density of DNA just by looking at what fraction of your DNA ever becomes a protein (only around 1 percent). But it’s not that simple. The rest of your DNA does other important things, like regulating what proteins get made. Some of it seems to exist only for the purpose of copying itself. Some of it might do nothing, or it might do important things we don’t even know about yet.

-

In the beginning, your DNA is relaxing in the nucleus.

-

Some parts of your DNA, called promoters, are designed so that if certain proteins are nearby, they’ll stick to the DNA.

-

If that happens, then a hefty little enzyme called “RNA polymerase” will show up, crack open the two strands of DNA, and start transcribing the nucleotides on one side into “pre-messenger RNA” (pre-mRNA).

-

Eventually, for one of several reasons—none of which make any sense to me—the enzyme will decide it’s time to stop transcribing, and the pre-mRNA will detach and float off into the nucleus. At this point, it’s a few thousand or a few tens of thousands of nucleotides long.

-

Then, my personal favorite macromolecular complex, the “spliceosome”, grabs the pre-mRNA, cuts away most of it, and throws those parts away. The sections of DNA that code for the parts that are kept are called exons, while the sections that code for parts that are thrown away are called introns.

-

Next, another enzyme called “RNA guanylyltransferase” (we can’t all be beautiful) adds a “cap” to one end, and an enzyme called “poly(A) polymerase” adds a “tail” to the other end.

-

The pre-mRNA is now all grown up and has graduated to being regular mRNA. At this point, it is a few hundred or a few thousand nucleotides long.

-

Then, some proteins notice that the mRNA has a tail, grab it, and throw it out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where the noble ribosome lurks.

-

The ribosome grabs the mRNA and turns it into a protein. It does this by starting at one end and looking at chunks of three nucleotides at a time, called "codons". When it sees a certain "start" pattern, it starts translating each chunk into one of 20 amino acids and continues until it sees a chunk with a "stop" pattern3.

-

The resulting protein lives happily ever after.

It’s thought that ~1 percent of your DNA is exons and ~24 percent is introns. What’s the rest of it doing?

Well, while the above dance is happening, other sections of DNA are “regulating” it. Enhancers are regions of DNA where a certain protein can bind and cause the DNA to physically bend so that some promoter somewhere else (typically within a million nucleotides) is more likely to get activated. Silencers do the opposite. Insulators block enhancers and silencers from influencing regions they shouldn’t influence.

While that might sound complicated, we’re just warming up. The same region of DNA can be both an intron and an enhancer and/or a silencer. That’s right, in the middle of the DNA that codes for some protein, evolution likes to put DNA that regulates some other, distant protein. When it’s not regulating, it gets transcribed into (probably useless) pre-RNA and then cut away and recycled by the spliceosome.

There's also structural DNA that's needed to physically manipulate the chromosomes. Centromeres are "attachment points" used when copying DNA during cell division. Telomeres are "extra" DNA at the ends of the chromosomes4.

Further complicating this picture are many regions of DNA that code for RNA that’s never translated into a protein but still has some function. Some regions make tRNA, whose job is to bring amino acids to the ribosome. Other regions make rRNA, which bundle together with some proteins to become the ribosome. There’s siRNA, microRNA, and piRNA that screw around with mRNA produced. And there’s scaRNA, snoRNA, rRNA, lncRNA, and mrRNA. Many more types are sure to be defined in the future, both because it’s hard to know for sure if DNA gets transcribed, it’s hard to know what functions RNA might have, and because academics have strong incentives to invent ever-finer subcategories.

There are also pseudogenes. These are regions of DNA that almost make proteins, but not quite. Sometimes, this happens because they lack a promoter, so they never get transcribed into mRNA. Other times, they might lack a start codon, so after their mRNA makes it to the ribosome, it never actually starts making a protein. Then, there are instances when the DNA has an early stop codon or a "frameshift" mutation meaning the alignment of the RNA into chunks of three gets screwed up. In these cases, the ribosome will often detect that something is wrong and call for help to destroy the protein. In other cases, a short protein is made that doesn't do anything5.

Why? Why is this all such a mess? Why is it so hard to say if a given section of DNA does anything useful?

Biologists hate “why” questions. We can’t re-run evolution, so how can we say “why” evolution did things the way it did? Better to focus on how biological systems actually work. This is probably wise. But since I’m not a biologist (or wise), I’ll give my theory: Cells work like this because DNA is under constant attack from mutations.

Mutations most commonly arise during cell replication. Your DNA is composed of around 250 billion atoms. Making a perfect copy of all those atoms is hard. Your body has amazing nanomachines with many redundant mechanisms to try to correct errors, and it’s estimated that the error rate is less than one per billion nucleotides. But with several billion nucleotides, mutations happen.

There are also environmental sources of mutations. Ultraviolet light has more energy than visible light. If it hits your skin, that energy can sort of knock atoms out of place. The same thing happens if you’re exposed to radiation. Certain chemicals, like formaldehyde, benzene, or asbestos, can also do this or can interfere with your body’s error correction tricks.

Finally, we return to the huge fraction of your DNA (~50-60 percent) that repeats of the same sequences. Some of this is caused by the machinery "slipping" while making a copy, leading to a loss or repetition of some DNA. There are also little sections of DNA called "transposons" that sort of trick your machinery into making another copy of those sections and then inserting them somewhere else in the genome67.

Mutations in your regular cells will just affect you, but mutations in your sperm/eggs could affect all future generations. Evolution helps manage this through selection. Say you have 10 bad mutations, and I have 10 bad mutations, but those mutations are in different spots. If we have some babies together, some of them might get 13 bad mutations, but some might only get 7, and the latter babies are more likely to pass on their genes.

But as well as selection, cells seem designed to be extremely robust to these kinds of errors. Instead of just relying on selection, there are many redundant mechanisms to tolerate them without much issue.

And remember, evolution is a madman. If it decides to tolerate some mutation, everything else will be optimized against it. So even if a mutation is harmful at first, evolution may later find a way to make use of it.

So, in theory, how should we define the “information content” of DNA? I propose a definition I call the “phenotypic Kolmogorov complexity”8. Roughly speaking, this is how short you could make DNA and still get a “human”.

The “phenotype” of an animal is just a fancy way of referring to its “observable physical characteristics and behaviors”. So this definition says, like Kolmogorov complexity, to try and find the shortest compressed representation of the DNA. But instead of needing to lead to the same DNA you have, it just needs to lead to an embryo that would look and behave like you do.

The idea is this: Take a single-cell human embryo with your DNA, and imagine all the different ways you can modify the DNA. This would include not only removing useless sections but also moving things around. Limit yourself to changes that still lead to a "person" that would still look like you and have all the same capabilities you do. Now, compress each of those representations. The smallest compressed representation is the "information" in your DNA9.

So what would this number be? My guess is that you could reduce the amount of DNA by at least 75 percent, but not by more than 98 percent, meaning the information content is:

12 billion bits

× 2 bits / nucleotide

× (2 to 25 percent)

= 480 million to 6 billion bits

= 60 MB to 750 MB

But in reality, nobody knows. We still have no idea what (if anything) lots of DNA is doing, and we’re a long way from fully understanding how much it can be reduced. Probably, no one will know for a long time.

Technically there’s also a tiny amount of DNA in the mitochondria. This is neat because you get it from your mother basically unchanged and so scientists can trace tiny mutations back to see how our great-great-…-great grandmothers were all related. If you go far enough back, our maternal lines all lead to a single woman, Mitochondrial Eve, who probably lived in East Africa 120,000 to 156,000 years ago. But mitochondrial DNA is tiny so I won’t mention it again.

Fun facts: Because of these deletions and insertions, different people have slightly different amounts of DNA. In fact, each of your chromosome pairs have DNA of slightly different lengths. When your body creates sperm/ova it uses a crazy machine to align the chromosomes in a sensible way so different sections can be woven together without creating nonsense. Also, those same measures of similarity would say that we’re around 96 percent identical with our closest living cousins, the bonobos and chimpanzees.

Since there are 4 kinds of nucleotides, there are 4³=64 possible chunks, while your body only uses 20 amino acids. So the ribosome, logically, gives some amino acids (like leucine) six different codons, and others (like tryptophan) only one codon. Also there are three different stop codons, but only one start codon, and that start codon is also the codon for methionine. So all proteins have methionine at one end unless something else comes and removes it later. Biology is layer after layer of this kind of exasperating complexity, totally indifferent to your desire to understand it.

Telomeres shrink as we age. The body has mechanisms to re-lengthen them, but it mostly only uses these in stem cells and reproductive cells. Longevity folks are interested in activating these mechanisms in other tissues to fight aging, but this is risky since the body seems to intentionally limit telomere repair as a strategy to prevent cancer cells from growing out of control.

In more serious cases, these mutations might make the organism non-viable, or lead to problems like Tay-Sachs disease or Cystic fibrosis. But this wouldn’t be considered a pseudogene.

“DNA transposons” get cut out and stuck back in somewhere else, while “retrotransposons” create RNA that’s designed to get reverse-transcribed back into the DNA in another location. There are also “retroviruses” like HIV that contain RNA that they insert into the genome. Some people theorize that retrotransposons can evolve into retroviruses and vice-versa.

It’s rare for retrotransposons to actually succeed in making a copy of themselves. They seem to have only a 1 in 100,000 or in 1,000,000 chance of copying themselves during cell division. But this is perhaps 10 times as high in the germ line, so the sperm from older men is more likely to contain such mutations.

This has surely been proposed by someone before, but I can’t find a reference, try as I might.

This definition isn’t totally precise, because I’m not saying how precisely the phenotype needs to match. Even if there’s some completely useless section of DNA and we remove it, that would make all your cells a tiny bit lighter. We need to tolerate some level of approximation. The idea is that it should be very close, but it’s hard to make this precise.