Why you should write more toy programs

I am a huge fan of Richard Feyman’s famous quote:

“What I cannot create, I do not understand”

I think it’s brilliant, and it remains true across many fields (if you’re willing to be a little creative with the definition of ‘create’). It is to this principle that I believe I owe everything I’m truly good at. Some will tell you to avoid reinventing the wheel, but they’re wrong: you should build your own wheel, because it’ll teach you more about how they work than reading a thousand books on them ever will.

In 2025, the beauty and craft of writing software is being eroded. AI is threatening to replace us (or, at least, the most joyful aspects of our craft) and software development is being increasingly commodified, measured, packaged, and industrialised. Software development needs more simple joy, and I’ve found that creating toy programs is a great way to remember why I started working with computers again.

Keep it simple

Toy programs follow the 80:20 rule: 20% of the work, 80% of the functionality. The point is not to build production-worthy software (although it is true that some of the best production software began life as a toy). Aggressively avoid over-engineering, restrict yourself to only whatever code is necessary to achieve your goal. Have every code path panic/crash until you’re forced to implement it to make progress. You might be surprised by just how easy it is to build toy versions of software you might previously have considered to be insummountably difficult to create.

Other benefits

I’ve been consistently surprised by just how often some arcane nugget of knowledge I’ve acquired when working on a toy project has turned out to be immensely valuable in my day job, either by giving me a head-start on tracking down a problem in a tool or library, or by recognising mistakes before they’re made.

Understanding the constraints that define the shape of software is vital for working with it, and there’s no better way to gain insight into those constraints than by running into them head-first. You might even come up with some novel solutions!

The list

Here is a list of toy programs I’ve attempted over the past 15 years, rated by difficulty and time required. These ratings are estimates and assume that you’re already comfortable with at least one general-purpose programming language and that, like me, you tend to only have an hour or two per day free to write code. Also included are some suggested resources that I found useful.

Regex engine (difficulty = 4/10, time = 5 days)

A regex engine that can read a POSIX-style regex program and recognise strings that match it. Regex is simple yet shockingly expressive, and writing a competent regex engine will teach you everything you need to know about using the language too.

x86 OS kernel (difficulty = 7/10, time = 2 months)

A multiboot-compatible OS kernel with a simple CLI, keyboard/mouse driver, ANSI escape sequence support, memory manager, scheduler, etc. Additional challenges include writing an in-memory filesystem, user mode and process isolation, loading ELF executables, and supporting enough video hardware to render a GUI.

GameBoy/NES emulator (difficulty = 6/10, time = 3 weeks)

A crude emulator for the simplest GameBoy or NES games. The GB and the NES are classics, and both have relatively simple instruction sets and peripheral hardware. Additional challenges include writing competent PPU (video) and PSG (audio) implementations, along with dealing with some of the more exotic cartridge formats.

GameBoy Advance game (difficulty = 3/10, time = 2 weeks)

A sprite-based game (top-down or side-on platform). The GBA is a beautiful little console to write code for and there’s an active and dedicated development community for the console. I truly believe that the GBA is one of the last game consoles that can be fully and completely understood by a single developer, right down to instruction timings.

Physics engine (difficulty = 5/10, time = 1 week)

A 2D rigid body physics engine that implements Newtonian physics with support for rectangles, circles, etc. On the simplest end, just spheres that push away from one-another is quite simple to implement. Things start to get complex when you introduce more complex shapes, angular momentum, and the like. Additional challenges include making collision resolution fast and scaleable, having complex interactions move toward a steady state over time, soft-body interactions, etc.

Dynamic interpreter (difficulty = 4/10, time = 1-2 weeks)

A tree-walking interpreter for a JavaScript-like language with basic flow control. There’s an unbounded list of extra things to add to this one, but being able to write programs in my own language still gives me child-like elation. It feels like a sort of techno-genesis: once you’ve got your own language, you can start building the universe within it.

Compiler for a C-like (difficulty = 8/10, time = 3 months)

A compiler for a simply-typed C-like programming language with support for at least one target archtecture. Extra challenges include implementing some of the most common optimisations (inlining, const folding, loop-invariant code motion, etc.) and designing an intermediate representation (IR) that’s general enough to support multiple backends.

Text editor (difficulty = 5/10, time = 2-4 weeks)

This one has a lot of variability. At the blunt end, simply reading and writing a file can be done in a few lines of Python. But building something that’s closer to a daily driver gets more complex. You could choose to implement the UI using a toolkit like QT or GTK, but I personally favour an editor that works in the console. Properly handling unicode, syntax highlighting, cursor movement, multi-buffer support, panes/windows, tabs, search/find functionality, LSP support, etc. can all add between a week or a month to the project. But if you persist, you might join the elite company of those developers who use an editor of their own creation.

Async runtime (difficulty = 6/10, time = 1 week)

There’s a lot of language-specific variability as to what ‘async’ actually means. In Rust, at least, this means a library that can ingest impl Future tasks and poll them concurrently until completion. Adding support for I/O waking makes for a fun challenge.

Hash map (difficulty = 4/10, time = 3-5 days)

Hash maps (or sets/dictionaries, as a higher-level language might call them) are a programmer’s bread & butter. And yet, surprisingly few of us understand how they really work under the bonnet. There are a plethora of techniques to throw into the mix too: closed or open addressing, tombstones, the robin hood rule, etc. You’ll gain an appreciation for when and why they’re fast, and also when you should just use a vector + linear search.

Rasteriser / texture-mapper (difficulty = 6/10, time = 2 weeks)

Most of us have played with simple 3D graphics at some point, but how many of us truly understand how the graphics pipeline works and, more to the point, how to fix it when it doesn’t work? Writing your own software rasteriser will give you that knowledge, along with a new-found appreciation for the beauty of vector maths and half-spaces that have applications across many other fields. Additional complexity involves properly implementing clipping, a Z-buffer, N-gon rasterisation, perspective-correct texture-mapping, Phong or Gouraud shading, shadow-mapping, etc.

SDF Rendering (difficulty = 5/10, time = 3 days)

Signed Distance Fields are a beautifully simple way to render 3D spaces defined through mathematics, and are perfectly suited to demoscene shaders. With relatively little work you can build yourself a cute little visualisation or some moving shapes like the graphics demos of the 80s. You’ll also gain an appreciation for shader languages and vector maths.

Voxel engine (difficulty = 5/10, time = 2 weeks)

I doubt there are many reading this that haven’t played Minecraft. It’s surprisingly easy to build your own toy voxel engine cut from a similar cloth, especially if you’ve got some knowledge of 3D graphics or game development already. The simplicity of a voxel engine, combined with the near-limitless creativity that can be expressed with them, never ceases to fill me with joy. Additional complexity can be added by tackling textures, more complex procedural generation, floodfill lighting, collisions, dynamic fluids, sending voxel data over the network, etc.

Threaded Virtual Machine (difficulty = 6/10, time = 1 week)

Writing interpreters is great fun. What’s more fun? Faster interpreters. If you keep pushing interpreters as far as they can go without doing architecture-specific codegen (like AOT or JIT), you’ll eventually wind up (re)discovering threaded code (not to be confused with multi-threading, which is a very different beast). It’s a beautiful way of weaving programs together out highly-optimised miniature programs, and a decent implementation can even give an AOT compiler a run for its money in the performance department.

GUI Toolkit (difficulty = 6/10, time = 2-3 weeks)

Most of us have probably cobbled together a GUI program using tkinter, GTK, QT, or WinForms. But why not try writing your GUI toolkit? Additional complexity involves implementing a competent layout engine, good text shaping (inc. unicode support), accessibility support, and more. Fair warning: do not encourage people to use your tool unless it’s battle-tested - the world has enough GUIs with little-to-no accessibility or localisation support.

Orbital Mechanics Sim (difficulty = 6/10, time = 1 week)

A simple simulation of Newtonian gravity can be cobbled together in a fairly short time. Infamously, gravitational systems with more than two bodies cannot be solved analytically, so you’ll have to get familiar with iterative integration methods. Additional complexity comes with implementing more precise and faster integration methods, accounting for relativistic effects, and writing a visualiser. If you’ve got the maths right, you can even try plugging in real numbers from NASA to predict the next high tide or full moon.

Bitwise Challenge (difficulty = 3/10, time = 2-3 days)

Here’s one I came up with for myself, but I think it would make for a great game jam: write a game that only persists 64 bits of state between subsequent frames. That’s 64 bits for everything: the entire frame-for-frame game state should be reproducible using only 64 bits of data. It sounds simple, but it forces you to get incredibly creative with your game state management. Details about the rules can be found on the GitHub page below.

An ECS Framework (difficulty = 4/10, time = 1-2 weeks)

For all those game devs out there: try building your own ECS framework. It’s not as hard as you might think (you might have accidentally done it already!). Extra points if you can build in safety and correctness features, as well as good integration with your programming language of choice’s type system features.

I built a custom ECS for my Super Mario 64 on the GBA project due to the unique performance and memory constraints of the platform, and enjoyed it a lot.

CHIP-8 Emulator (difficulty = 3/10, time = 3-6 days)

The CHIP-8 is a beautifully simple virtual machine from the 70s. You can write a fully compliant emulator in a day or two, and there are an enormous plethora of fan-made games that run on it. Here’s a game I made for it.

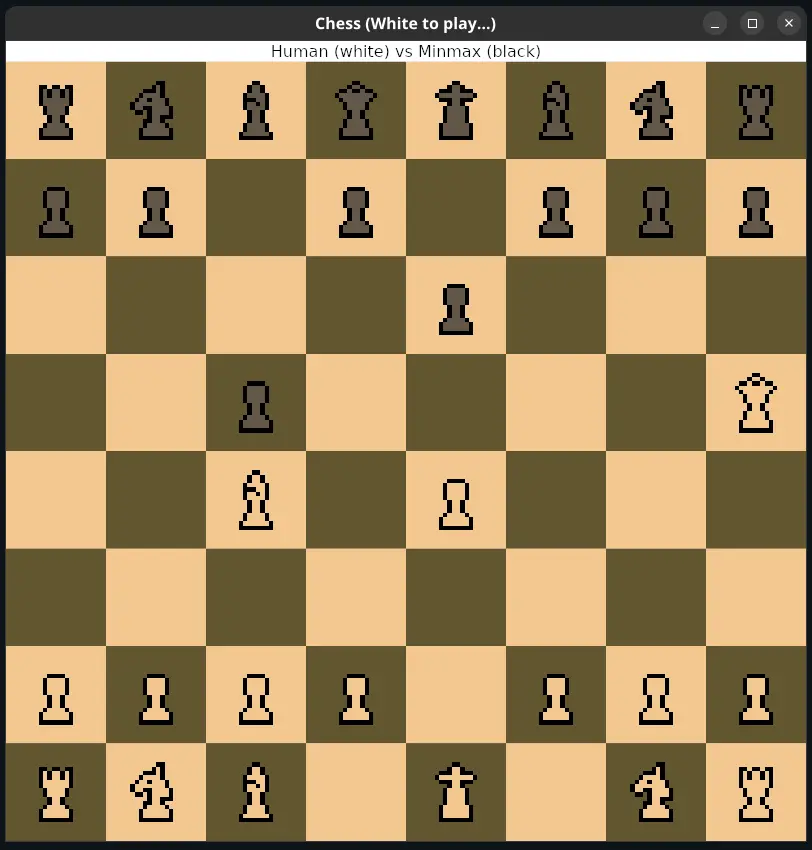

Chess engine (difficulty = 5/10, time = 2-5 days)

Writing a chess engine is great fun. You’ll start off with every move it makes being illegal, but over time it’ll get smart and smarter. Experiencing a loss to your own chess engine really is a rite of passage, and it feels magical.

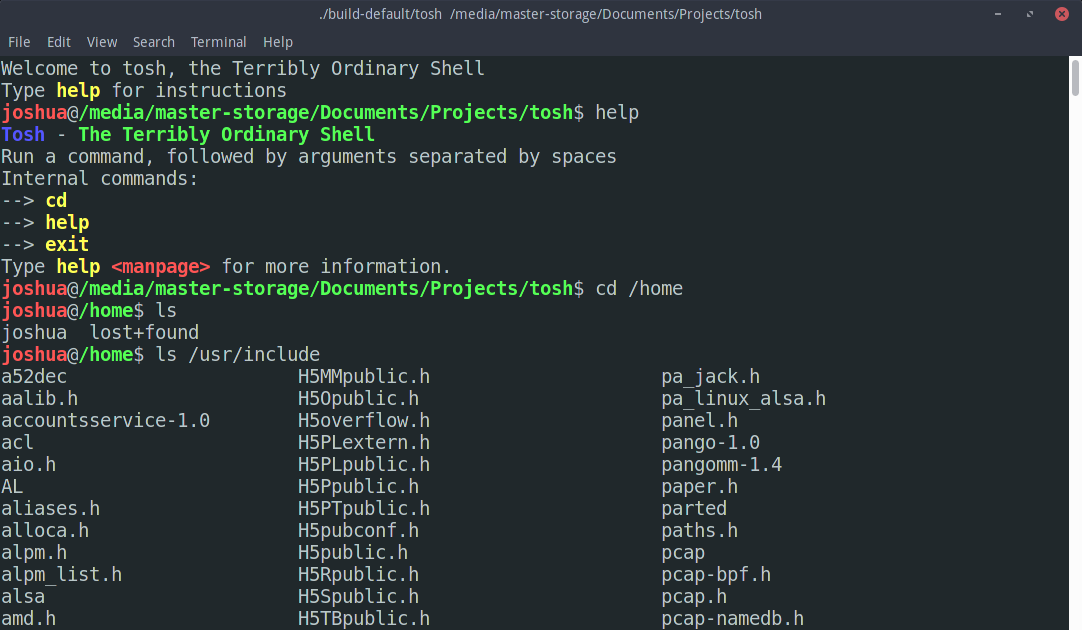

POSIX shell (difficulty = 4/10, time = 3-5 days)

We interact with shells every day, and building one will teach you can incredible amount about POSIX - how it works, and how it doesn’t. A simple one can be built in a day, but compliance with an existing shell language will take time and teach you more than you ever wanted to know about its quirks.

A note on learning and LLMs

Perhaps you’re a user of LLMs. I get it, they’re neat tools. They’re useful for certain kinds of learning. But I might suggest resisting the temptation to use them for projects like this. Knowledge is not supposed to be fed to you on a plate. If you want that sort of learning, read a book - the joy in building toy projects like this comes from an exploration of the unknown, without polluting one’s mind with an existing solution. If you’ve been using LLMs for a while, this cold-turkey approach might even be painful at first, but persist. There is no joy without pain.

The runner’s high doesn’t come to those that take the bus.