8 days ago

Anna Bressanin

Alamy

Alamy

(Credit: Alamy)

When one of Italy's much-loved Five Towers toppled, it seemed a rare, exceptional event. In fact, throughout this stunning mountain range, peaks are crumbling.

True to its name, the Five Towers – a small, iconic mountain range in the Dolomites (Eastern Italian Alps) – resembled five stone fingers spreading up towards the sky. One night between 4 and 7 June 2004, one of them, the Trephor Tower, came down. The Rifugio Scoiattoli – a chalet so close by that patrons can easily stroll to touch the rocks even after eating too much polenta – hadn't opened for the summer season yet, so no one heard a thing. One morning, they saw the Trephor, a monolith of more than 10,000 cubic metres – the size of the leaning Tower of Pisa without the bells and the tourists – lying down horizontally.

Today, Antonio Galgaro, an associate professor of geosciences at the University of Padua, believes he can predict which tower will be next. "It's like a panettone divided in four slices. This one," says Galgaro, indicating one of the peaks on an aerial picture, "will start to detach from the main block and rotate, until it comes down". The English Tower already shows an evident diagonal crack where the rock is likely to break and slide down, like a child on a banister.

Through the summer of 2025, news of landslides interrupting the main road in the region that will host the next Winter Olympics has dropped nearly every week. On 15 June, Francesco Accardo, a local resident who lives about 20m [65ft] from the gully of Mount Antelao, saw "rocks as big as cars flying down the ravine, bouncing and rebounding".

About two hours out of Venice, the Unesco Natural Heritage Site of the Dolomites is widely regarded as the most stunning mountain range in Italy and one of the most attractive in the world. As an Italian who spent most of my childhood holidays in the area, over the past few months I've found myself wondering whether the entire Dolomites are coming down. If they are, can we do anything about it?

How the panettone comes down

Since the Trephor fell, many significant collapses have been recorded in the Dolomites. To note some of the most spectacular ones reported by local press: the Grand Vernel (2015), Piccola Croda Rossa (2015 and 2016), Cima Lastei (2016), Carè Alto (2018), Croda Marcora (2021 and 2025), and Sassolungo and Cima Tosa (2023). Videos and photos show big chunks of mountain coming down, pinnacles toppling, and debris flows rolling down the slope like rocky rivers.

Falling is in the nature of these dramatic mountains. The Dolomites were once ancient tropical atolls in the deep ocean that rose up when the European and African tectonic plates collided hundreds of millions of years ago. Underneath the dolomia stone, there is a soft layer of clay.

"It has the consistency of Das," Galgaro says, referring to an artificial playdough popular in Italy in the 1980s, similar to a malleable grey terracotta.

Every mountain guide will tell you that, in fact, you feel like you are walking on something much more fragile than before – Giovanni Crosta

Let's take the Five Towers as a case study.

The rock monoliths both tilt and rotate under the force of gravity as they settle on the soft clay below. The result is visible from above. "It looks like a flower, each tower slightly inclined outwards," says Galgaro.

Once one side of a tower sinks a bit deeper than the other side, it creates a diagonal crack, along which the rock eventually breaks, slides down and falls.

Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti

Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti

The Trephor Tower, one of the Five Towers that no longer stands – seen here before and after its fall (Credit: Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti)

The idea of a mountain being fixed solidly in place is a misconception.

"The DNA of every mountain is to come down," says Giovanni Crosta, a professor in geology at University of Milan-Bicocca, who studies the relation between climate and landslides in the Alps. "It's the destiny of every vertical thing."

That's how the steep Dolomites landscape took its shape – big pieces of rock fell, leaving spires looking like a villain's castle in a Disney movie. The debris created gravelly slopes.

In Belluno alone, the largest of the five Dolomites provinces, 6,133 significant landslides interrupting traffic and affecting villages have been recorded since the Middle Ages. Of course, many more events might have been forgotten, not recorded, or otherwise fallen through the cracks of history. Because of this incomplete record, it is not easy for scientists to be sure whether or not large rockfalls are increasing rapidly in recent times.

Bandion.it

Bandion.it

Still, even though erosion is natural, primeval and inevitable, there is now a general feeling of acceleration among locals and experts, and only partly because of the media attention drawn to the area ahead of the 2026 Winter Olympics. "Every mountain guide will tell you that, in fact, you feel like you are walking on something much more fragile than before," says Crosta.

The radiator effect

Crosta's team looks at the correlation between landslides and other events such as heavy rains, which are among the most common triggers of landslides. "We can see a concerning increase of intense, short rainfalls," says Eleonora Dallan, assistant professor of environmental engineering at the University of Padua.

Extreme rainfall events are set to become more frequent. Specifically, Dallan has found the maximum precipitation values have grown by 5-20% in the past 30-40 years.

Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti

Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti

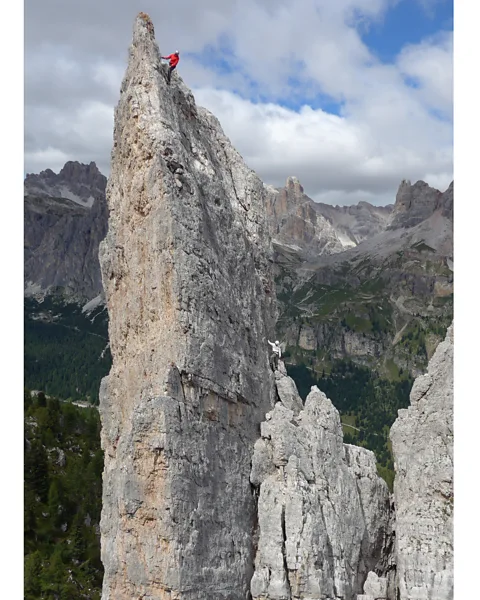

The English Tower, pictured, could be the next of the Five Towers to fall (Credit: Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti)

Water flows into cracks, freezes, expands and eventually breaks the rock. "The fracturing of the rock due to the freeze-thaw cycle has augmented in recent years," says Francesco Comiti, an associate professor at the University of Padua who studies the impact of sediments on rivers. And it doesn’t stop there.

"Fracturing results in more rapid heating and cooling phenomena, which can be detected with infrared thermal cameras." says Galgaro. "This assessment helps us understand how far the rock mass is separated from the more stable portion and thus indicates the susceptibility to collapse."

As rainwater infiltrates fractures, or when ice in the rock thaws to liquid, it can act as a trigger on unstable rock masses, Galgaro says, "causing even massive detachments from the walls of mountain ranges".

To explain the heating acceleration, Galgaro uses the metaphor of a radiator. The more the rock cracks, it both releases warmth and gets cold faster than if it were a single solid block – just like a radiator does a good job at warming a room because it is made of many hot separated elements, each doing their bit.

Some good news for the Dolomites, and for whoever wants them to stay up as they are, is that they are not as tall as the rest of the Alps. Taller peaks, and northern slopes, often have permafrost – a "glue" of frozen moisture within the soil and rock – that is now thawing at greater rates due to climate change.

Peak Faulkner, for instance, which stands at 2,999m (9,839ft), collapsed on 27 July and 1 August 2025. Around 300,000-400,000 cubic metres of rock came down. But many mountains in the region are shorter and have no permafrost to start with.

Although landslides have been observed for hundreds of years in this region, the main overall issue, according to Crosta, is now unpredictability and frequence. The forecast models and knowledge that have guided humans in building houses and streets, allowing them to inhabit these extraordinary mountains for centuries, are not accurate nor valid anymore. "Think of someone who manages these lands. What do they do now? Do they leave a certain path open? Or do they move it 50-100m [165-330ft] further down to be safe?"

Living with falling rock

In terms of solutions, Galgaro uses the Italian idiom "the patch is worse than the hole" – a sartorial metaphor discouraging well-meaning attempts to fix problems in ways that could cause bigger problems down the line.

"My belief is that nature can only be accompanied," says Galgaro. "You can't bridle it, or oppose it, because in the end, nature always wins."

Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti

Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti

Local people and visitors to the Dolomites face the danger of rockfall and landslide (Credit: Enrico Maioni/ Guide Dolomiti)

He mentions Eni village, a modernist town built in the 1950s, and added last year to a list of sites of cultural interest in the region. The utopian village was built very close to the path of debris from the slopes of Mount Antelao. Rockfalls from the mountain have claimed two lives in the village of Cancia.

Instead of bridling the mountain, scientists now focus on monitoring and alerting the population. Galgaro's team, for instance, records the vibration of the mountains and converts it into a sound that is audible to human ears. "It's like a candy wrapper", he says, describing the seconds before a major collapse.

Crosta's team is closely observing a pinnacle in the Pisciadu, part of the Sella group. Half of a monolith there came down in 2018. "Now, only a thin spire, an 80m-tall (260ft) blade is left up there," says Crosta. "The part behind it already fell down. It's obvious that it's a sensitive spot."

A map database managed by Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research records all the landslides ever recorded in Italy with the goal of raising awareness, when buying a house for instance.

Crosta also mentions the Goûter Route up Mont Blanc, part of which is known as the Route of Death due to high risk of rockfall. "They thought of any possible solution: rockfall nets, structures… but there are so many blocks falling down, and so often, and the area is so wide that it is impossible [to control]. Now, they are thinking of just opening the cableways earlier, so that Alpine climbers can come and take that path earlier in the morning, when the conditions are less dangerous".

Basically, more than a solution to stop the fall, it's a matter of learning to live with the risk.

Alpine guide Enrico Maioni, has been climbing the Five Towers and other majestic peaks in the Dolomites for 51 years, since he was 14. "I'm not afraid of falling. After all these years, I know my limits – I know what I can and can't do," he says. "But if a rock wall collapses on your head, there's not much you can do. Still, he adds, "my work is a passion. It's imponderable. It's not like I'd quit now."

Whoever has spent some time on these mountains, like me, might feel nostalgic about losing even one of these peaks and their familiar, wondrous shapes. Here are three thoughts that might help. First, some erosions reveal wonders themselves: like the ancient grey and pale blue glacier that reappeared a year ago under the debris flow of Mountain Pelmo, according to Italy's National Associated Press Agency.

Second, although it's undoubtedly sad that one of the Five Towers came down, there were actually 12 towers to start with – they got shortchanged on the name because only five are visible against the sky from below. So, the fact that the number of towers doesn't match its official name is nothing new.

Third, as Crosta notes, the Dolomites are a natural Unesco World Heritage Site, not a cultural one – and, by definition, nature evolves. "It would be nonsense to try and prevent a natural site from the action of nature," says Crosta.

In other words, we can't cement these mountains to keep them in the shape we know and love. True, some of these changes, and their acceleration, are the result of human impact on Earth. "But to stop that, you'd have to go back and change everything," he says.

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.