TL;DR

A malicious GitHub Actions workflow was pushed to a shared repo and exfiltrated a npm token with broad publish rights. The attacker then used that token to publish malicious versions of 20 packages, including @ctrl/tinycolor.

My GitHub account, the @ctrl/tinycolor repository were not directly compromised. There was no phishing involved, and no malicious packages were installed on my machine and I already use pnpm to avoid unapproved postinstall scripts. There was no pull request involved because a repo admin does not need a pull request to add new github actions.

GitHub/npm security responded quickly, unpublishing the malicious versions. I followed by releasing clean versions to flush caches, as advised.

For broader context, see Socket’s write-up or StepSecurity’s analysis. For community discussion, see this Hacker News post, which spent 24 hours on the front page. I’m also finding this wiz.io post helpful.

How I Found Out

On September 15 around 4:30 PM PT, Wes Todd DM’d me on Bluesky and looped me into the OpenJS Foundation Slack. By that point, Wes had already alerted GitHub/npm security, who were compiling lists of affected packages and rapidly unpublishing compromised versions.

Early guidance (attributed to Daniel Pereira) was to look for suspicious Shai-Hulud repos or branches. I wasn’t able to find any of these repos or branches on my own personal repos. The mystery was: how was I impacted at all?

Shai-Hulud was the Fremen term for the sandworm of Arrakis. - dune wiki

What Actually Happened

A while ago, I collaborated on angulartics2, a shared repository where multiple people still had admin rights. That repo still contained a GitHub Actions secret — a npm token with broad publish rights. This collaborator had access to projects with other people which I believe explains some of the other 40 initial packages that were affected.

A new Shai-Hulud branch was force pushed to angulartics2 with a malicious github action workflow by a collaborator. The workflow ran immediately on push (did not need review since the collaborator is an admin) and stole the npm token. With the stolen token, the attacker published malicious versions of 20 packages. Many of which are not widely used, however the @ctrl/tinycolor package is downloaded about 2 million times a week.

GitHub and npm security teams moved quickly to unpublish the malicious versions. I then re-published fresh, verified versions of the packages I maintain to flush caches and restore trust.

Impact

Malicious versions of several packages — including @ctrl/tinycolor — were briefly available on npm before removal. Installing those compromised versions would have triggered a postinstall payload, which is documented in detail by StepSecurity.

What should you do if you’ve installed a compromised version of a package? see StepSecurity’s immediate actions.

Publishing Setup & Interim Plan

I currently use semantic-release with GitHub Actions to handle publishing. The automation is convenient and predictable. I also have npm provenance enabled on many packages, which provides attestations of how they were built. Unfortunately, provenance didn’t prevent this attack because the attacker had a valid token.

My goal is to move to npm’s Trusted Publishing (OIDC) to eliminate static tokens altogether. However, semantic-release integration is still in progress: npm/cli#8525.

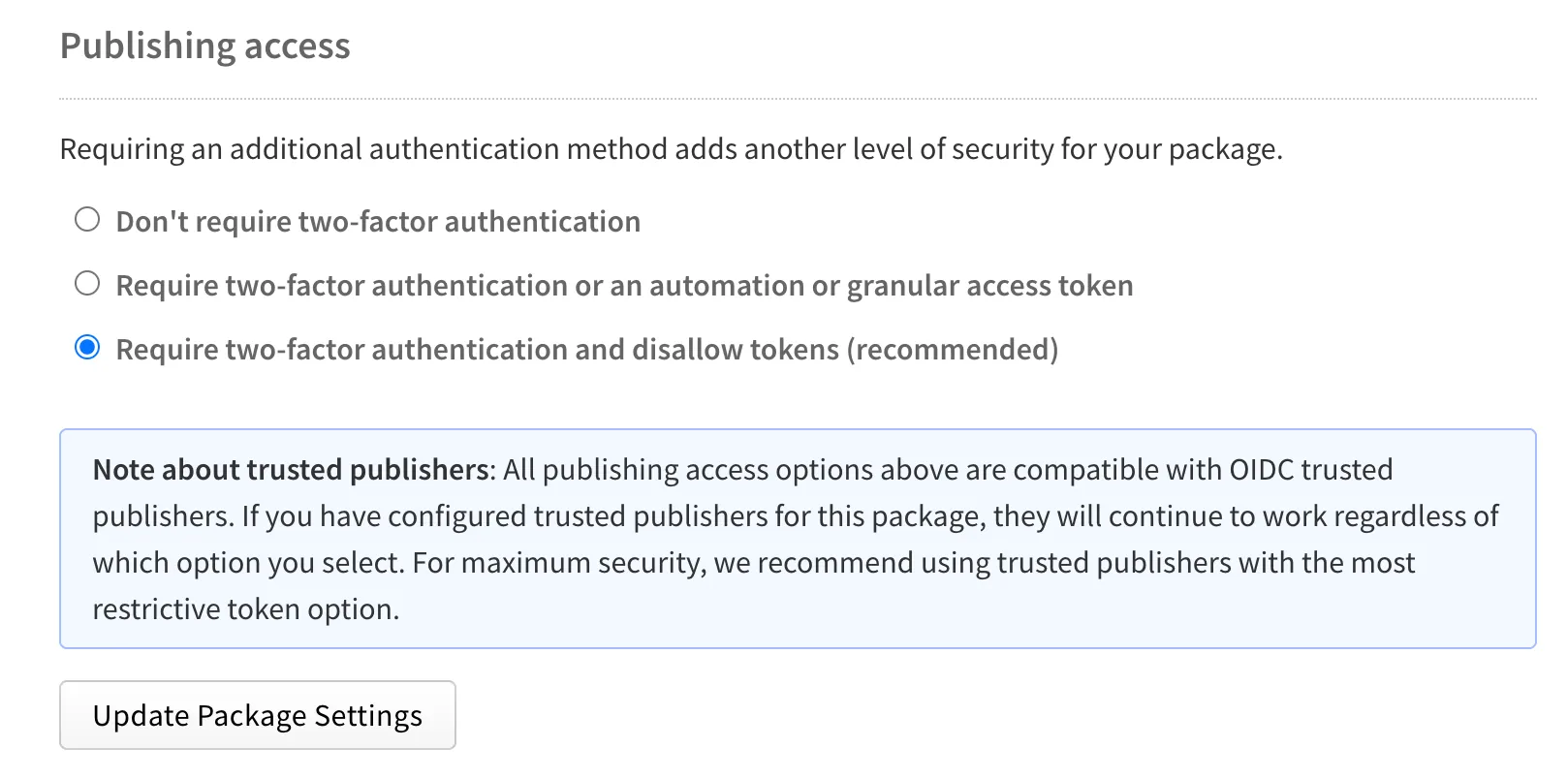

For the forseeable future, @ctrl/tinycolor requires 2FA for publishing, and all tokens have been revoked. Not expecting to merge any new changes anytime soon.

For smaller packages, I’ll continue using semantic-release but under stricter controls: no new contributors will be added, and each repo will use a granular npm token limited to publish-only rights for that specific package.

Local 2FA based publishing isn’t sustainable, so I’m watching OIDC/Trusted Publishing closely and will adopt it as soon as it fits the workflow.

I plan to continue using pnpm that prevents unapproved postinstall scripts from being run and I’ll look into adding pnpm’s new minimumReleaseAge setting.

Publishing Wishlist

If I could wave a magic wand and design my ideal setup, npm would allow me to require Trusted Publishing (OIDC) with a single toggle for all of my packages. That same toggle would block any release missing provenance, enforcing security at the account level. I’d also want first-class semantic-release support with OIDC and provenance so no static tokens are ever needed.

On top of that, I’d like a secure, human-approved publishing option directly in the GitHub UI: a protected workflow_dispatch flow that uses github 2FA approval to satisfy 2FA, without requiring me to publish from my laptop.

GitHub Environments — or equivalent workflow protections — should be available without a Pro subscription, or else integrated directly into Trusted Publishing so that security doesn’t depend on the pricing tier.

It would be really nice if NPM also had a more visible mark on the package details page to indicate if the package had a postinstall script. Also, once the packages are pulled its not clear what versions were removed and why.

Thanks

Thanks to Wes Todd, the OpenJS Foundation, and the GitHub/npm security teams for their rapid and coordinated response. Everyone was incredibly fast, helpful, and knowledgeable.

![dune worm [wide] | dune worm via chatgpt](https://sigh.dev/_astro/dune-worm.QN2JLFkT_ZOy594.webp)