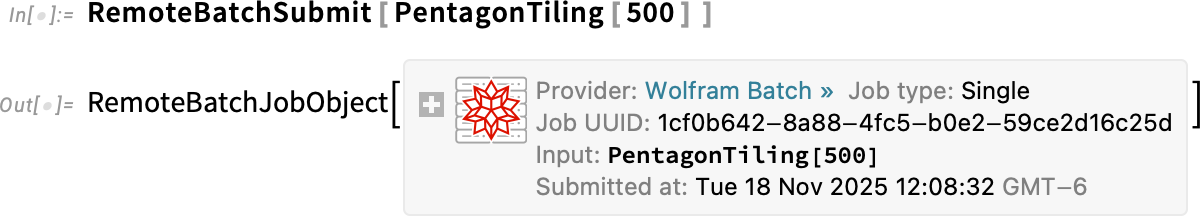

To immediately enable Wolfram Compute Services in Version 14.3 Wolfram Desktop systems, run

RemoteBatchSubmissionEnvironment["WolframBatch"]

.

(The functionality is automatically available in the Wolfram Cloud.)

Scaling Up Your Computations

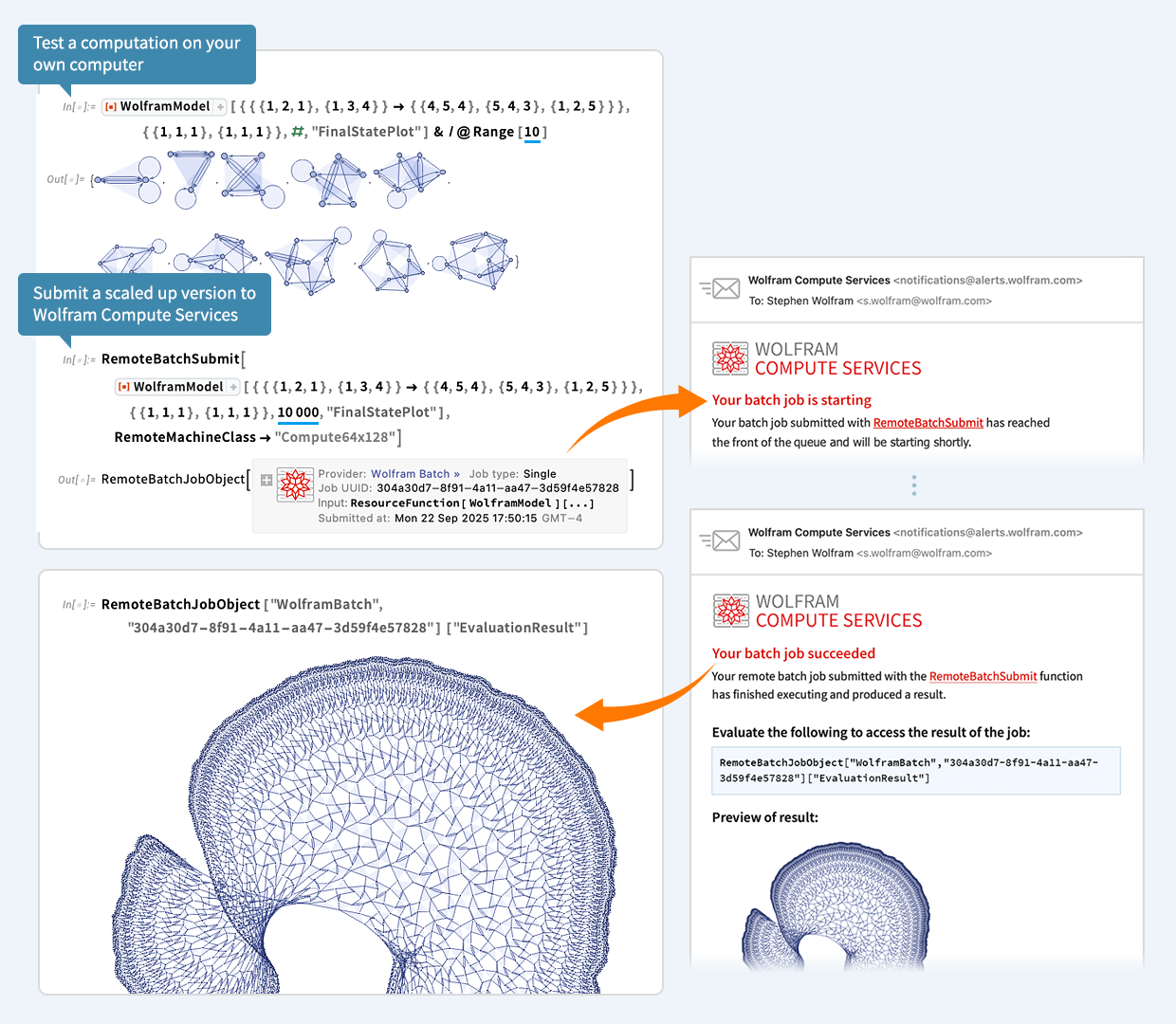

Let’s say you’ve done a computation in Wolfram Language. And now you want to scale it up. Maybe 1000x or more. Well, today we’ve released an extremely streamlined way to do that. Just wrap the scaled up computation in RemoteBatchSubmit and off it’ll go to our new Wolfram Compute Services system. Then—in a minute, an hour, a day, or whatever—it’ll let you know it’s finished, and you can get its results.

For decades I’ve often needed to do big, crunchy calculations (usually for science). With large volumes of data, millions of cases, rampant computational irreducibility, etc. I probably have more compute lying around my house than most people—these days about 200 cores worth. But many nights I’ll leave all of that compute running, all night—and I still want much more. Well, as of today, there’s an easy solution—for everyone: just seamlessly send your computation off to Wolfram Compute Services to be done, at basically any scale.

For nearly 20 years we’ve had built-in functions like ParallelMap and ParallelTable in Wolfram Language that make it immediate to parallelize subcomputations. But for this to really let you scale up, you have to have the compute. Which now—thanks to our new Wolfram Compute Services—everyone can immediately get.

The underlying tools that make Wolfram Compute Services possible have existed in the Wolfram Language for several years. But what Wolfram Compute Services now does is to pull everything together to provide an extremely streamlined all-in-one experience. For example, let’s say you’re working in a notebook and building up a computation. And finally you give the input that you want to scale up. Typically that input will have lots of dependencies on earlier parts of your computation. But you don’t have to worry about any of that. Just take the input you want to scale up, and feed it to RemoteBatchSubmit. Wolfram Compute Services will automatically take care of all the dependencies, etc.

And another thing: RemoteBatchSubmit, like every function in Wolfram Language, is dealing with symbolic expressions, which can represent anything—from numerical tables to images to graphs to user interfaces to videos, etc. So that means that the results you get can immediately be used, say in your Wolfram Notebook, without any importing, etc.

OK, so what kinds of machines can you run on? Well, Wolfram Compute Services gives you a bunch of options, suitable for different computations, and different budgets. There’s the most basic 1 core, 8 GB option—which you can use to just “get a computation off your own machine”. You can pick a machine with larger memory—currently up to about 1500 GB. Or you can pick a machine with more cores—currently up to 192. But if you’re looking for even larger scale parallelism Wolfram Compute Services can deal with that too. Because RemoteBatchMapSubmit can map a function across any number of elements, running on any number of cores, across multiple machines.

A Simple Example

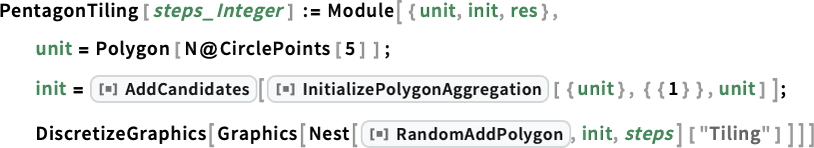

OK, so here’s a very simple example—that happens to come from some science I did a little while ago. Define a function PentagonTiling that randomly adds nonoverlapping pentagons to a cluster:

For 20 pentagons I can run this quickly on my machine:

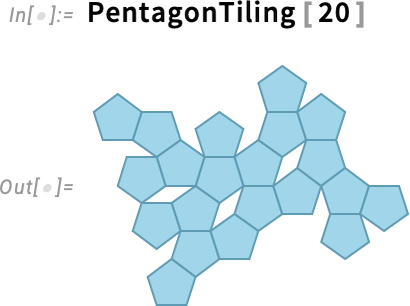

But what about for 500 pentagons? Well, the computational geometry gets difficult and it would take long enough that I wouldn’t want to tie up my own machine doing it. But now there’s another option: use Wolfram Compute Services!

And all I have to do is feed my computation to RemoteBatchSubmit:

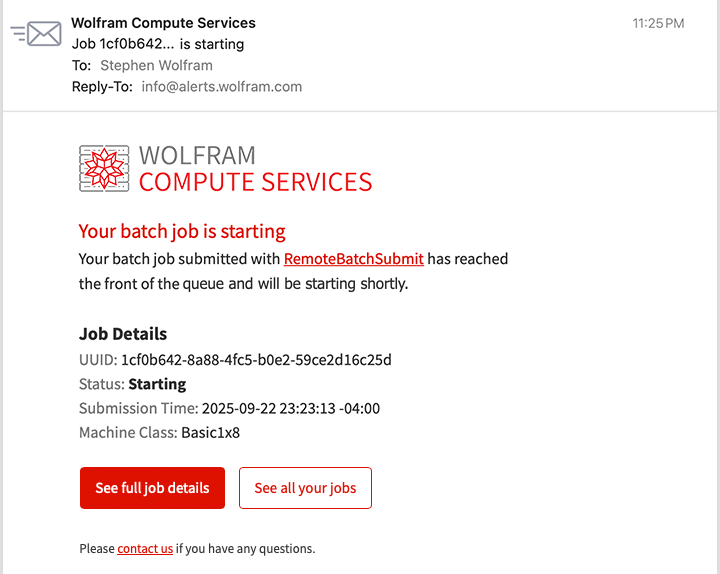

Immediately, a job is created (with all necessary dependencies automatically handled). And the job is queued for execution. And then, a couple of minutes later, I get an email:

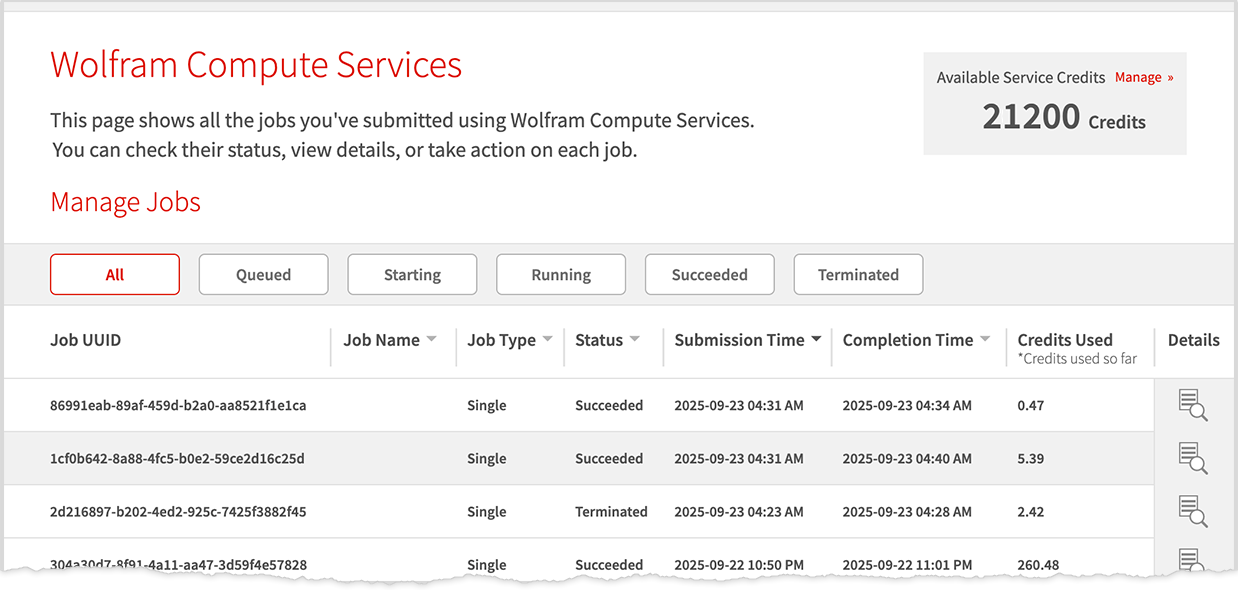

Not knowing how long it’s going to take, I go off and do something else. But a while later, I’m curious to check how my job is doing. So I click the link in the email and it takes me to a dashboard—and I can see that my job is successfully running:

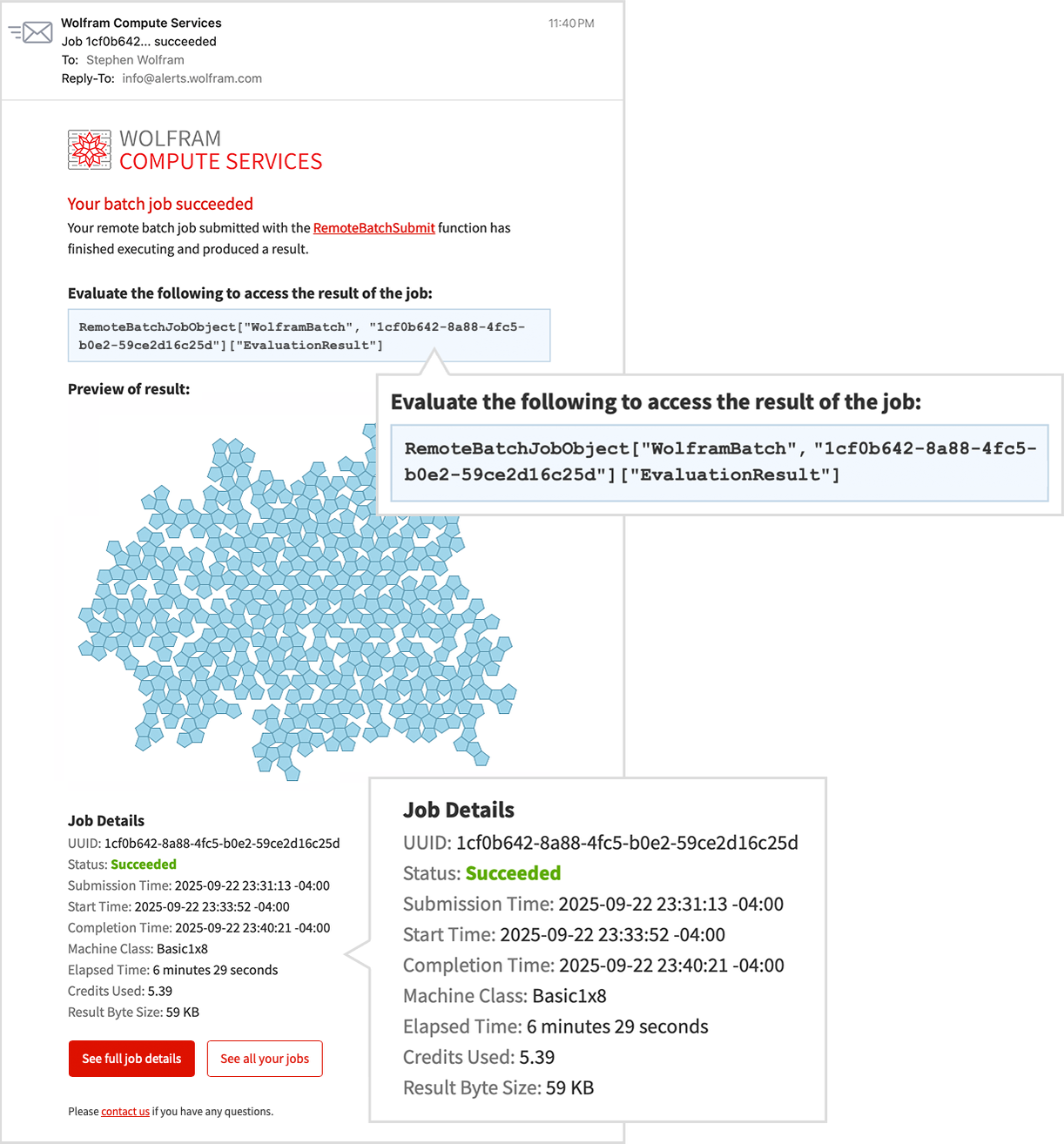

I go off and do other things. Then, suddenly, I get an email:

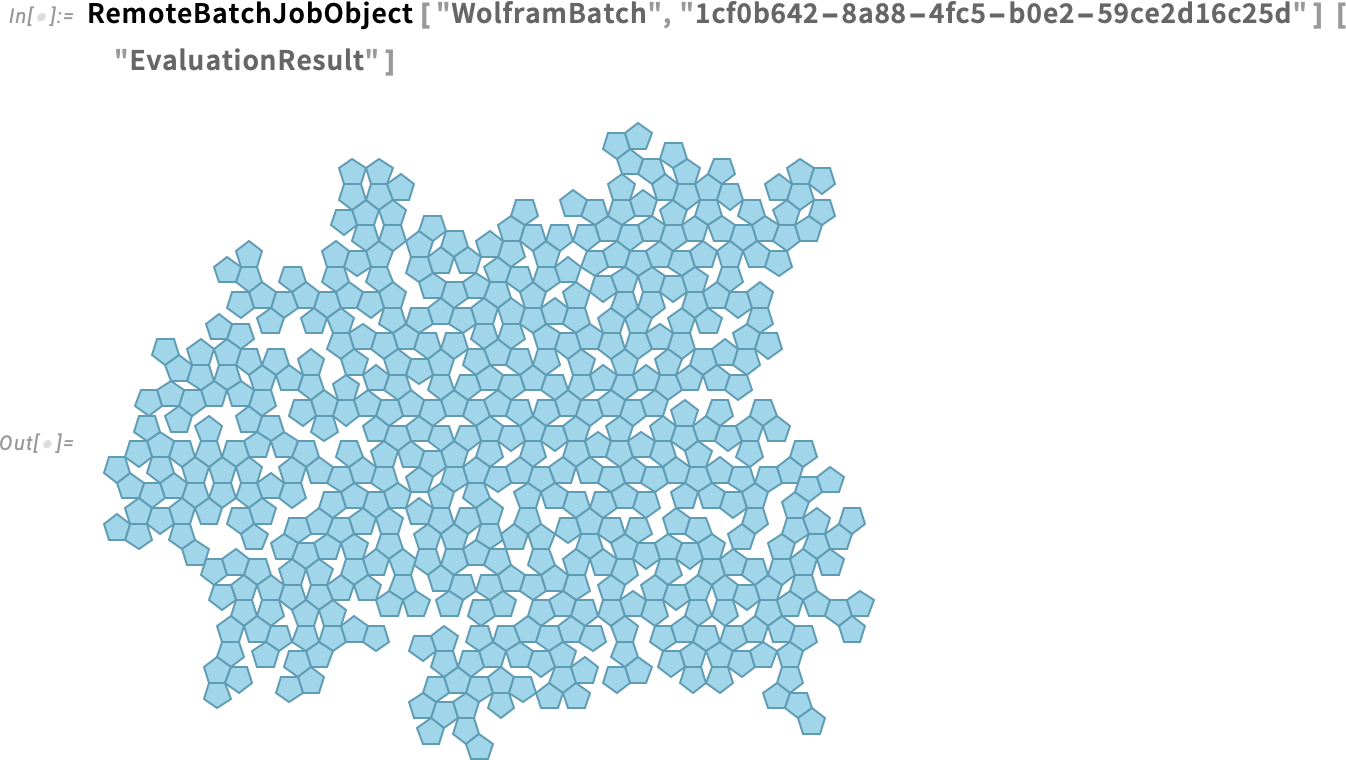

It finished! And in the mail is a preview of the result. To get the result as an expression in a Wolfram Language session I just evaluate a line from the email:

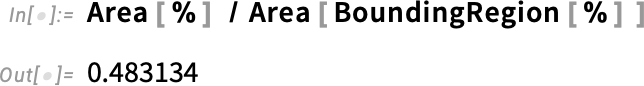

And this is now a computable object that I can work with, say computing areas

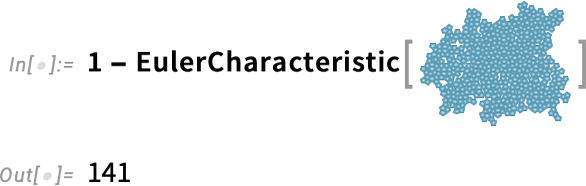

or counting holes:

Large-Scale Parallelism

One of the great strengths of Wolfram Compute Services is that it makes it easy to use large-scale parallelism. You want to run your computation in parallel on hundreds of cores? Well, just use Wolfram Compute Services!

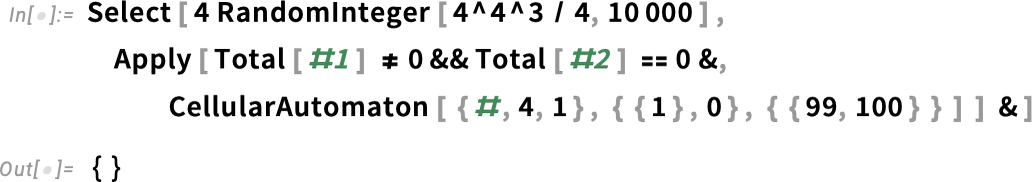

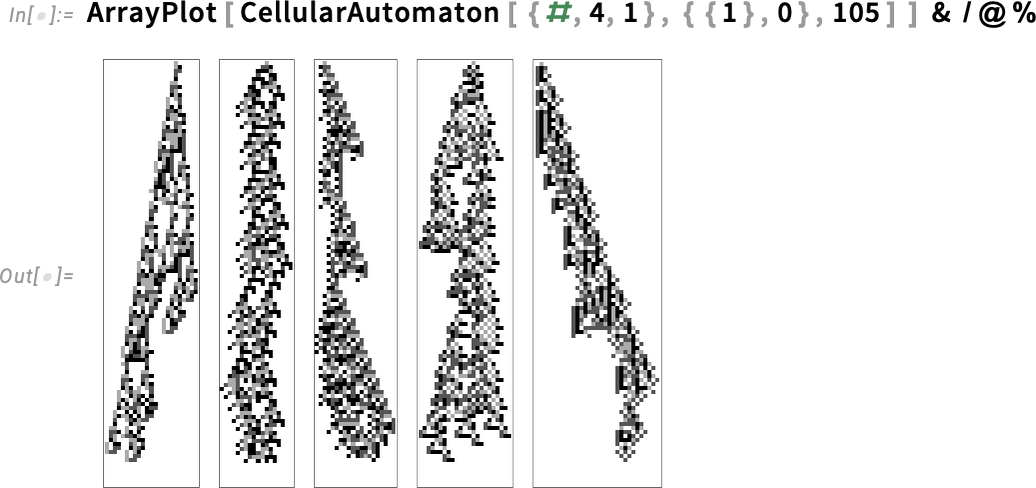

Here’s an example that came up in some recent work of mine. I’m searching for a cellular automaton rule that generates a pattern with a “lifetime” of exactly 100 steps. Here I’m testing 10,000 random rules—which takes a couple of seconds, and doesn’t find anything:

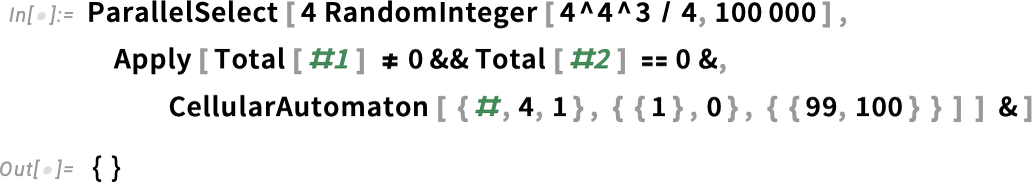

To test 100,000 rules I can use ParallelSelect and run in parallel, say across the 16 cores in my laptop:

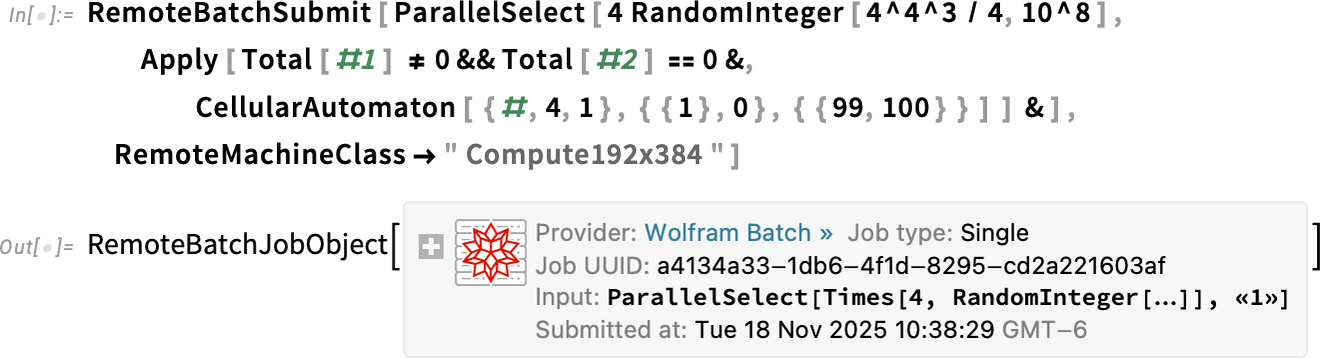

Still nothing. OK, so what about testing 100 million rules? Well, then it’s time for Wolfram Compute Services. The simplest thing to do is just to submit a job requesting a machine with lots of cores (here 192, the maximum currently offered):

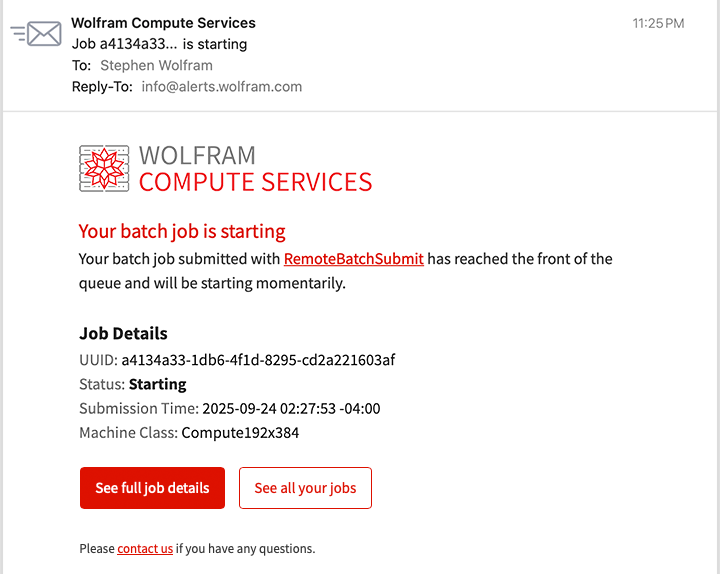

A few minutes later I get mail telling me the job is starting. After a while I check on my job and it’s still running:

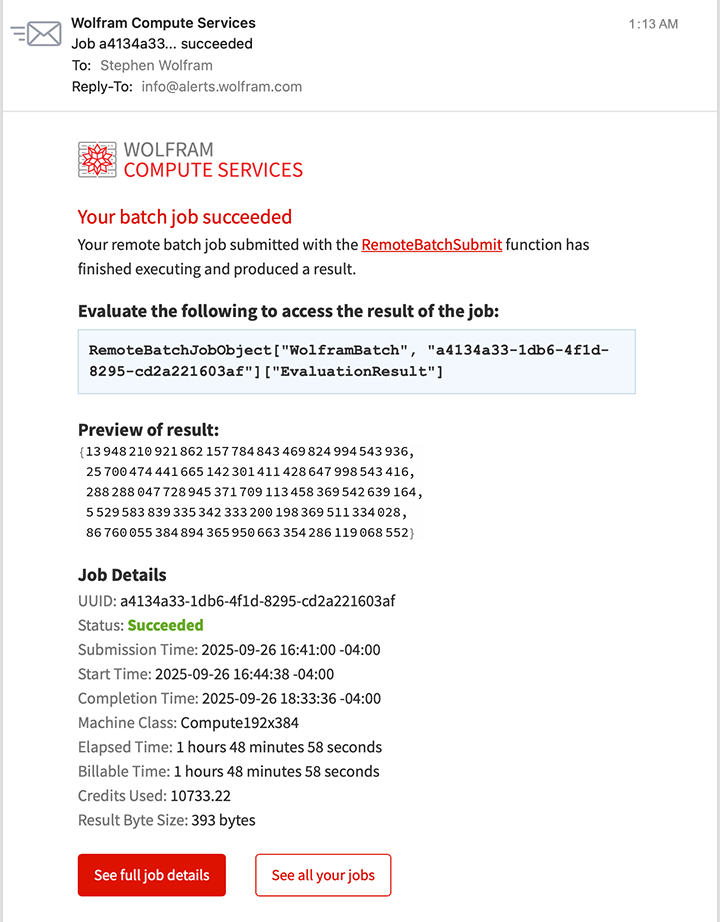

I go off and do other things. Then, after a couple of hours I get mail telling me my job is finished. And there’s a preview in the email that shows, yes, it found some things:

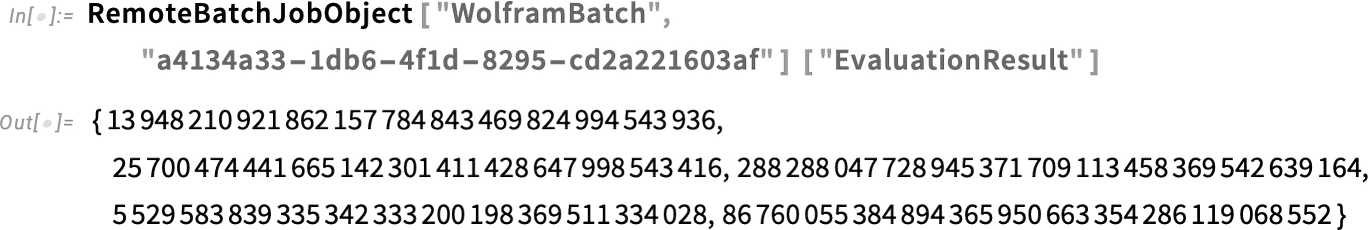

I get the result:

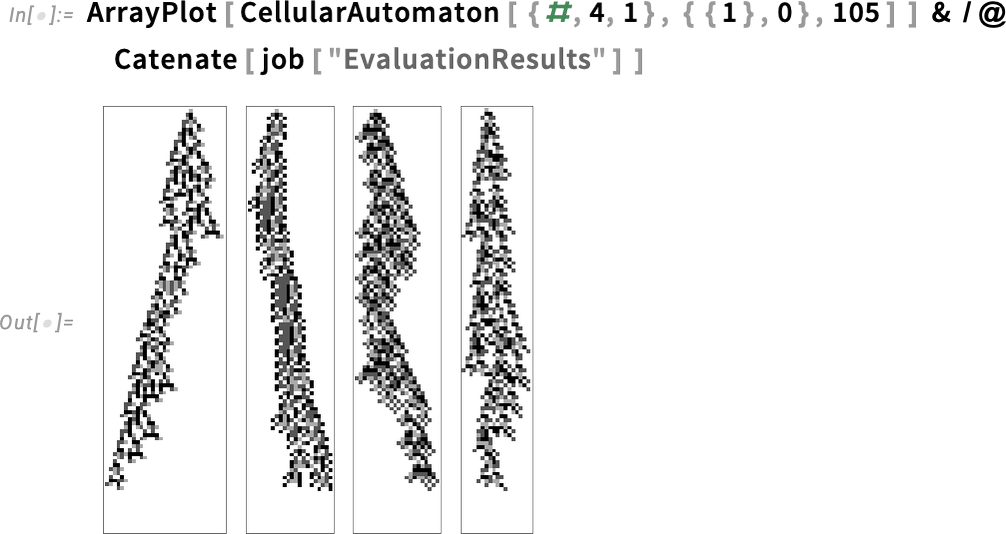

And here they are—rules plucked from the hundred million tests we did in the computational universe:

But what if we wanted to get this result in less than a couple of hours? Well, then we’d need even more parallelism. And, actually, Wolfram Compute Services lets us get that too—using RemoteBatchMapSubmit. You can think of RemoteBatchMapSubmit as a souped up analog of ParallelMap—mapping a function across a list of any length, splitting up the necessary computations across cores that can be on different machines, and handling the data and communications involved in a scalable way.

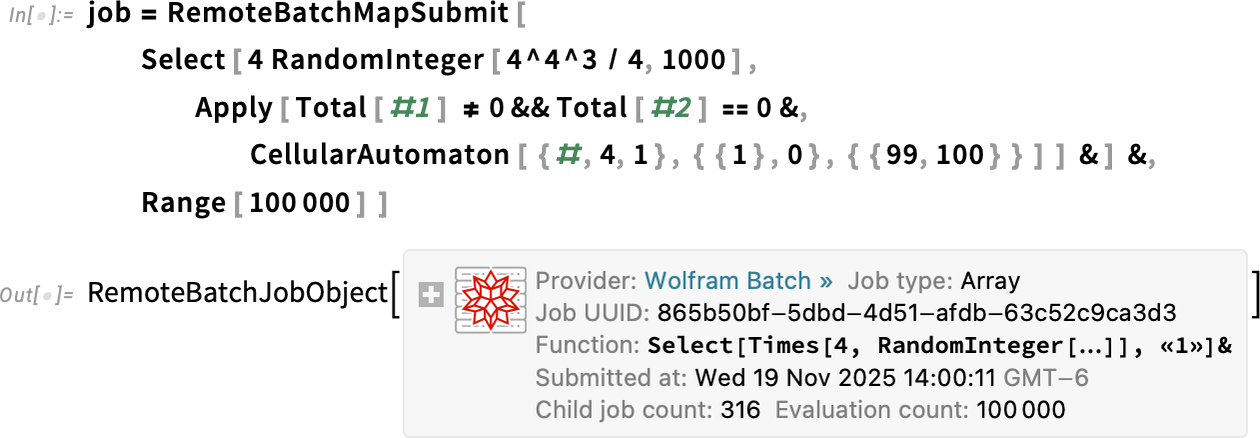

Because RemoteBatchMapSubmit is a “pure Map” we have to rearrange our computation a little—making it run 100,000 cases of selecting from 1000 random instances:

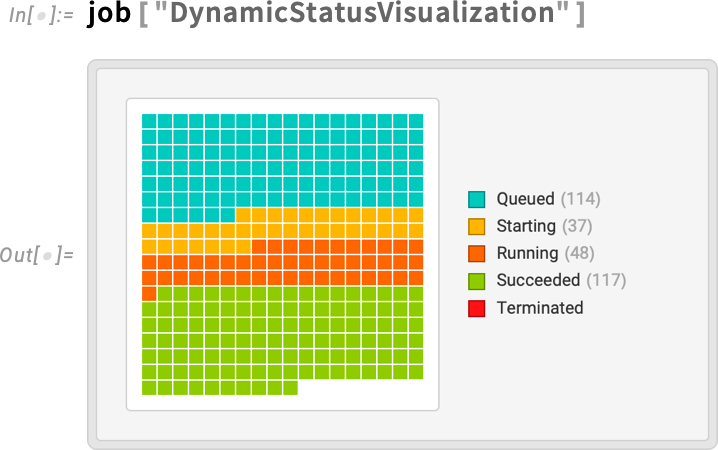

The system decided to distribute my 100,000 cases across 316 separate “child jobs”, here each running on its own core. How is the job doing? I can get a dynamic visualization of what’s happening:

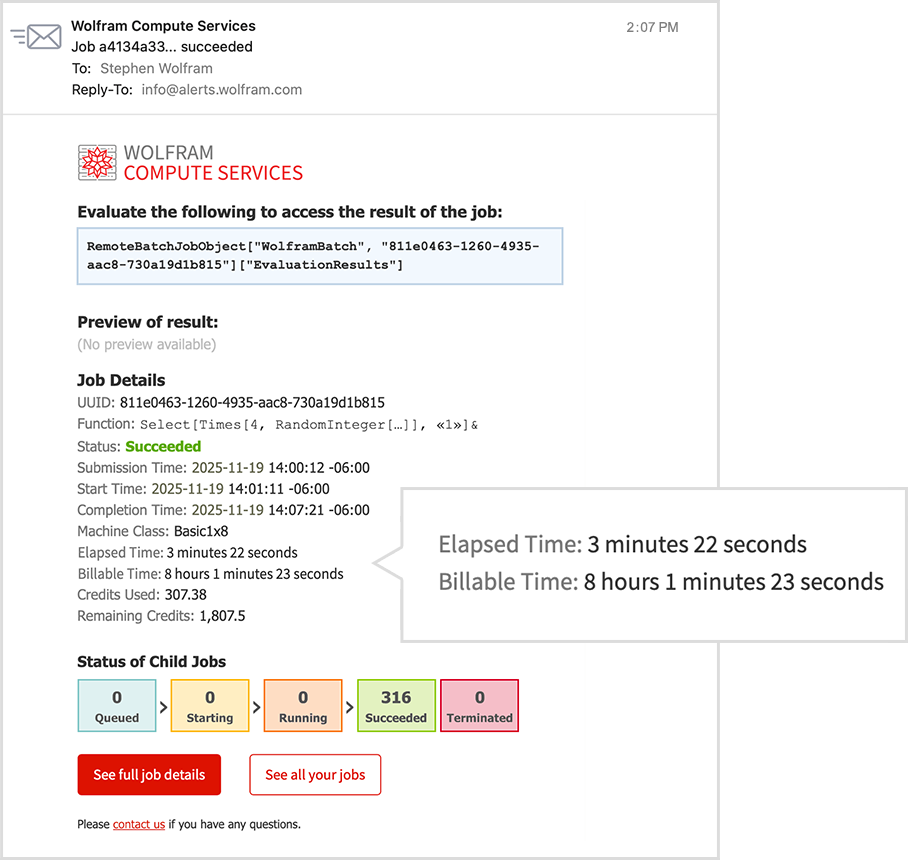

And it doesn’t take many minutes before I’m getting mail that the job is finished:

And, yes, even though I only had to wait for 3 minutes to get this result, the total amount of computer time used—across all the cores—is about 8 hours.

Now I can retrieve all the results, using Catenate to combine all the separate pieces I generated:

And, yes, if I wanted to spend a little more, I could run a bigger search, increasing the 100,000 to a larger number; RemoteBatchMapSubmit and Wolfram Compute Services would seamlessly scale up.

It’s All Programmable!

Like everything around Wolfram Language, Wolfram Compute Services is fully programmable. When you submit a job, there are lots of options you can set. We already saw the option RemoteMachineClass which lets you choose the type of machine to use. Currently the choices range from "Basic1x8" (1 core, 8 GB) through "Basic4x16" (4 cores, 16 GB) to “parallel compute” "Compute192x384" (192 cores, 384 GB) and “large memory” "Memory192x1536" (192 cores, 1536 GB).

Different classes of machine cost different numbers of credits to run. And to make sure things don’t go out of control, you can set the options TimeConstraint (maximum time in seconds) and CreditConstraint (maximum number of credits to use).

Then there’s notification. The default is to send one email when the job is starting, and one when it’s finished. There’s an option RemoteJobName that lets you give a name to each job, so you can more easily tell which job a particular piece of email is about, or where the job is on the web dashboard. (If you don’t give a name to a job, it’ll be referred to by the UUID it’s been assigned.)

The option RemoteJobNotifications lets you say what notifications you want, and how you want to receive them. There can be notifications whenever the status of a job changes, or at specific time intervals, or when specific numbers of credits have been used. You can get notifications either by email, or by text message. And, yes, if you get notified that your job is going to run out of credits, you can always go to the Wolfram Account portal to top up your credits.

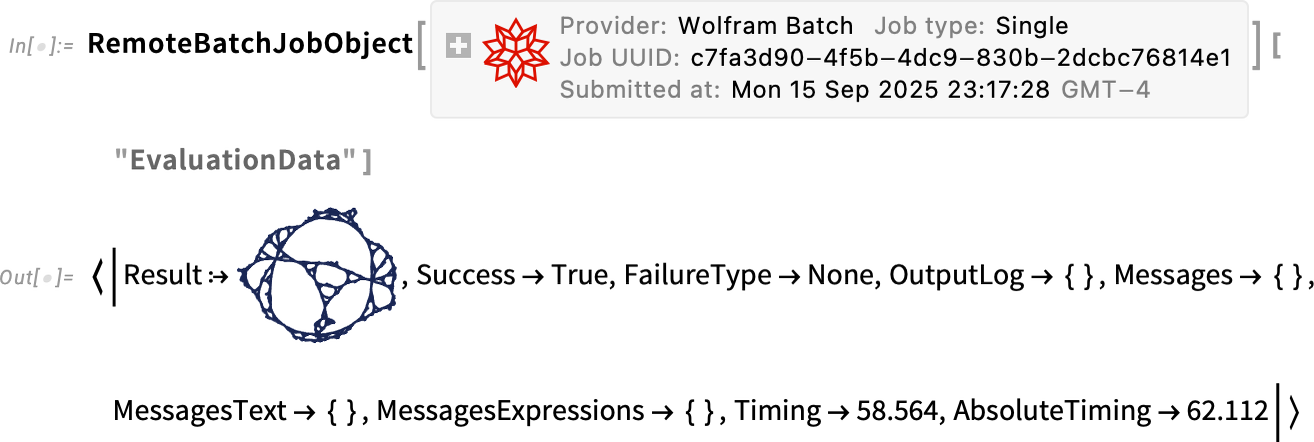

There are many properties of jobs that you can query. A central one is "EvaluationResult". But, for example, "EvaluationData" gives you a whole association of related information:

If your job succeeds, it’s pretty likely "EvaluationResult" will be all you need. But if something goes wrong, you can easily drill down to study the details of what happened with the job, for example by looking at "JobLogTabular".

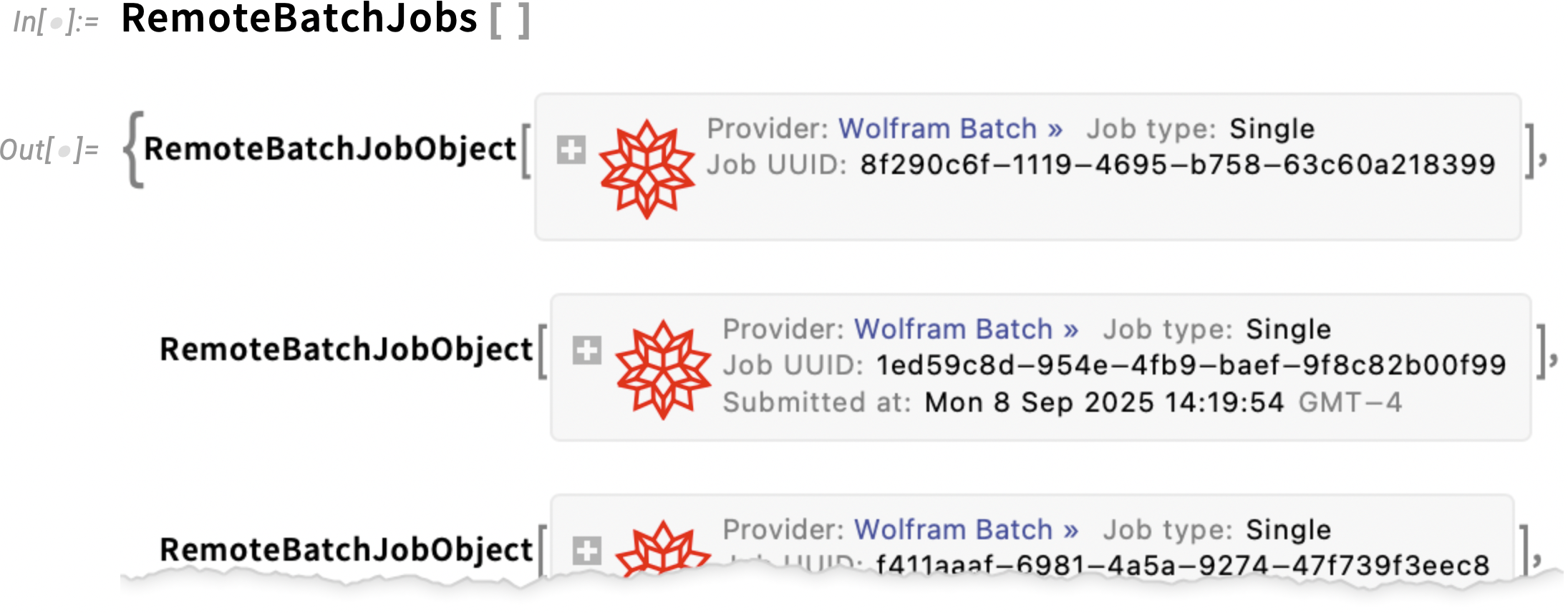

If you want to know all the jobs you’ve initiated, you can always look at the web dashboard, but you can also get symbolic representations of the jobs from:

For any of these job objects, you can ask for properties, and you can for example also apply RemoteBatchJobAbort to abort them.

Once a job has completed, its result will be stored in Wolfram Compute Services—but only for a limited time (currently two weeks). Of course, once you’ve got the result, it’s very easy to store it permanently, for example, by putting it into the Wolfram Cloud using CloudPut[expr]. (If you know you’re going to want to store the result permanently, you can also do the CloudPut right inside your RemoteBatchSubmit.)

Talking about programmatic uses of Wolfram Compute Services, here’s another example: let’s say you want to generate a compute-intensive report once a week. Well, then you can put together several very high-level Wolfram Language functions to deploy a scheduled task that will run in the Wolfram Cloud to initiate jobs for Wolfram Compute Services:

And, yes, you can initiate a Wolfram Compute Services job from any Wolfram Language system, whether on the desktop or in the cloud.

And There’s More Coming…

Wolfram Compute Services is going to be very useful to many people. But actually it’s just part of a much larger constellation of capabilities aimed at broadening the ways Wolfram Language can be used.

Mathematica and the Wolfram Language started—back in 1988—as desktop systems. But even at the very beginning, there was a capability to run the notebook front end on one machine, and then have a “remote kernel” on another machine. (In those days we supported, among other things, communication via phone line!) In 2008 we introduced built-in parallel computation capabilities like ParallelMap and ParallelTable. Then in 2014 we introduced the Wolfram Cloud—both replicating the core functionality of Wolfram Notebooks on the web, and providing services such as instant APIs and scheduled tasks. Soon thereafter, we introduced the Enterprise Private Cloud—a private version of Wolfram Cloud. In 2021 we introduced Wolfram Application Server to deliver high-performance APIs (and it’s what we now use, for example, for Wolfram|Alpha). Along the way, in 2019, we introduced Wolfram Engine as a streamlined server and command-line deployment of Wolfram Language. Around Wolfram Engine we built WSTPServer to serve Wolfram Engine capabilities on local networks, and we introduced WolframScript to provide a deployment-agnostic way to run command-line-style Wolfram Language code. In 2020 we then introduced the first version of RemoteBatchSubmit, to be used with cloud services such as AWS and Azure. But unlike with Wolfram Compute Services, this required “do it yourself” provisioning and licensing with the cloud services. And, finally, now, that’s what we’ve automated in Wolfram Compute Services.

OK, so what’s next? An important direction is the forthcoming Wolfram HPCKit—for organizations with their own large-scale compute facilities to set up their own back ends to RemoteBatchSubmit, etc. RemoteBatchSubmit is built in a very general way, that allows different “batch computation providers” to be plugged in. Wolfram Compute Services is initially set up to support just one standard batch computation provider: "WolframBatch". HPCKit will allow organizations to configure their own compute facilities (often with our help) to serve as batch computation providers, extending the streamlined experience of Wolfram Compute Services to on-premise or organizational compute facilities, and automating what is often a rather fiddly job process of submission (which, I must say, personally reminds me a lot of the mainframe job control systems I used in the 1970s).

Wolfram Compute Services is currently set up purely as a batch computation environment. But within the Wolfram System, we have the capability to support synchronous remote computation, and we’re planning to extend Wolfram Compute Services to offer this—allowing one, for example, to seamlessly run a remote kernel on a large or exotic remote machine.

But this is for the future. Today we’re launching the first version of Wolfram Compute Services. Which makes “supercomputer power” immediately available for any Wolfram Language computation. I think it’s going to be very useful to a broad range of users of Wolfram Language. I know I’m going to be using it a lot.