For many of our e-commerce customers the problem of bad bots it's a everyday problem and has evolved a lot in the last few years. A common approach is to "block" automated traffic with a JavaScript challenge, basically a small script that the browser must execute to prove it is a real client... Yes, this works well against primitive scrapers, but it no longer stops modern bot based on real browsers and human-like gestures. Tools like Selenium, Puppeteer, and Playwright can execute the challenge inside a full Chromium instance, covering themself by disabling the classic navigator.webdriver = true flag. So, the idea of "My JavaScript code has been executed so the user must be human" stopped being reliable a long time ago.

If you think this problem can be solved with a CAPTCHA the answer is NO! Damn, no. If you think so, you usually fall into one of two categories: The first one is not knowing that the most widely used CAPTCHAs can be solved automatically, and that entire "human solver" farms exist for the sole purpose of solving CAPTCHA on behalf of bots. There are well known services like 2Captcha, Anti Captcha, CapMonster, DeathByCaptcha, and many others that deliver thousands of solved challenges per minute for a few cents. The second and the most important point is user experience. Forcing users to solve a CAPTCHA every time they add an item to the cart or take an action during checkout it's a mess for the buying flow process. Imagine Amazon asking you to solve a puzzle at login, then again asking you many times to select all "Bus photos" when adding a product to your cart, and again when confirming the purchase. No serious e-commerce platform would accept that level of user interaction.

The problem is that modern bots don't behave like stupid scripts (as you can imagine). Many of them uses full headless browsers, automate user interactions, and try to look as close as possible to a real user. But sometimes they expose themselves. Chromium in headless mode does not produce the same sec fetch metadata as a "normal" browser, and the User Agent Client Hints are often incomplete, mismatched, or missing.

What Client Hints are, where they come from?

Even today I see WAF rules like "let me check you User-Agent... oh yes, it start with Mozilla, you are a real browser!" this approach is not only stupid, but it's a waste of CPU for a website that receive millions of requests per hour. Anyway, why implementing client hints? Because the User-Agent header started as a simple information, then turned into a huge string full of details about browser, OS, device, and sometimes even patches and builds. That was useful for feature detection and compatibility, but it turned into a total fingerprinting disaster over time.

To fix this, the Chromium team introduced User-Agent Client Hints (UA-CH). Instead of dumping everything into one opaque string, the browser exposes small, structured pieces of information through dedicated headers like Sec-CH-UA, Sec-CH-UA-Platform, Sec-CH-UA-Mobile, and their "high-entropy" variants for full version, architecture, model, and platform version. Modern Chrome started experimenting with this around 2015 under the "Client Hints" umbrella for things like DPR and viewport, and then extended the idea to user agent identity as part of the User-Agent Reduction plan that rolled out from 2020 in stable versions.

Here come the cool part of having something like the UA client hints: by default, a Chromium based browser only exposes low-entropy hints, such as a generic brand list and a major version (like 140 and not 140.1.2.3.4.5 etc...), hiding OS info and build details. If a site really needs more information, it can send an header called Accept-CH response header with a list of client hints the website needs to do things. The browser can then decide to send richer hints on subsequent requests or not (usually it is totally transparent). This means that the first request comes to the website without client hints, and the all other requests comes with requested additional client hitns.

Another cool thing: Let say that the website really needs client hints even for the first request, it can send the header Critical-CH instead of or together with Accept-CH in order to make the browser internally reload the same page (with a 307 status) sending all required client hints. Provider like CloudFlare use this technique while sending their JavaScript Challenge (you can see them inspecting the response headers).

Ok but what changes for defenders?

From a security and detection perspective, this is interesting because a real browser keeps its identity stack consistent across UA, Client Hints, and JavaScript APIs, while headless setups and bad bots often fail to do so. That is exactly why many protection systems today lean on Client Hints, not just for content variations, but to tell the difference between an actual browser running on a real device and a """script""" that is only pretending to be a real human.

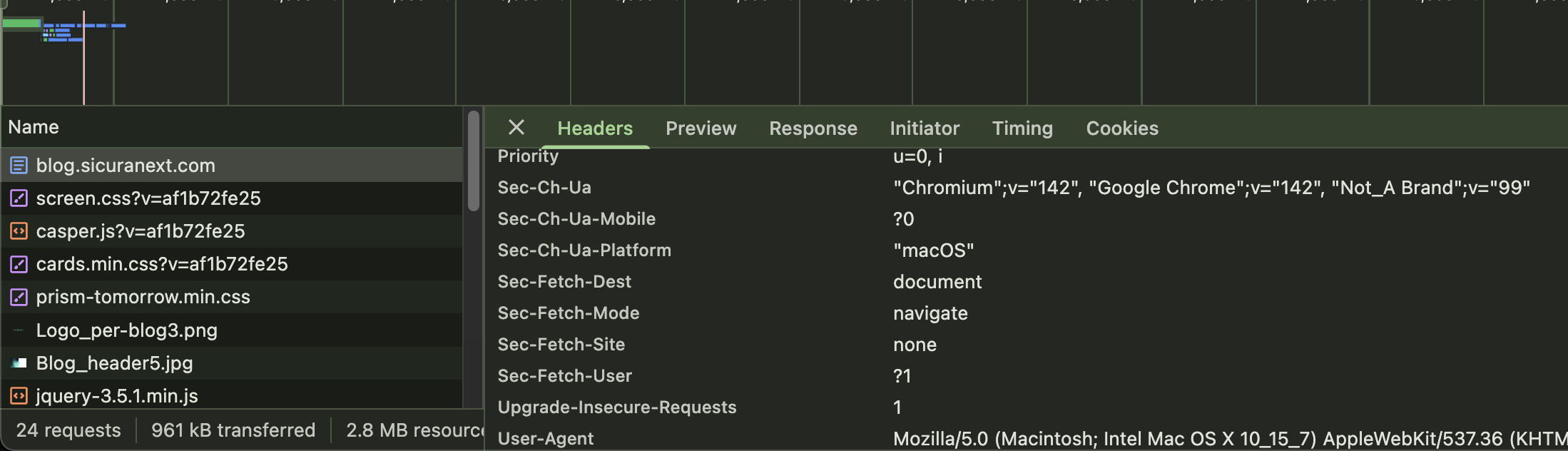

For example, while browsing this blog your Chrome would send:

These values are sent by default and are part of the modern "low-entropy identity". As I said before, you can see that my browser just sent the main version "142" without details about the build in the Sec-Ch-Ua header.

The cool thing is that, by reading CH and Sec-Fetch headers, I can say a lot about that request:

- it's a navigation started with a user action

- the user have entered the URL into the address bar

- it's a top level navigation requesting a HTML document

- the user is on a macOS using Google Chrome 142

- the user is navigating from a desktop (not a mobile)

- the user is super smart because he/she read very interesting blog post

Let start with CH-UA:

Sec-CH-UA: "Chromium";v="142", "Google Chrome";v="142", "Not_A Brand";v="99"

Sec-CH-UA-Mobile: ?0

Sec-CH-UA-Platform: "macOS"

What do they means?

Sec-CH-UA: This header contains the brand list, a structured representation of the browser identity. Chrome normally exposes three entries:

- "Chromium";v="142"

- "Google Chrome";v="142"

- "Not_A Brand";v="99"

The meaning is:

- Chromium identifies the open-source engine the browser is built on.

- Google Chrome is the actual product name.

- Not_A Brand is intentionally added as a "placeholder value". It exists only to prevent websites from strict parsing that list. The position of this value is random, could appear at the beginning or in the middle or at the end of the string.

The version numbers match the major version of the browser, which ensures internal consistency across CH and the user-agent string.

Sec-CH-UA-Mobile: ?0 This tells the server whether the browser is running on a mobile form-factor (?1) or not (?0). But, careful: this does not indicate if the OS is mobile or not, but it says if the browser prefers a mobile content. Chrome on macOS correctly returns ?0 but Android can have this set to ?0 when user requests a desktop version or on wide screen (and yes, this creates many funny edge cases in headless mode, where automation tools often get this wrong).

Sec-CH-UA-Platform: "macOS" is the platform identity according to the Client Hints model. Chrome only exposes a short information of the OS, not the detailed version number (unless the server explicitly requests high-entropy hints).

So, what can we do with those information? For example: an inconsistent combination like "macOS" + "?1" or "Android" + "Win64" is one of the easiest ways to spot automation tools or browser instrumentation.

Last week I was digging into a traffic spike during a client's ticket drop... it was kind of funny seeing a bot claiming to be an iPhone 15 while its headers were screaming "I'm a Linux server in an AWS datacenter" lol 😄.

Now, let's talk about Sec-Fetch-*

Understanding the Sec-Fetch-* headers

Modern browsers expose a small set of request headers called Fetch Metadata Request Headers, introduced around 2019–2020 and gradually adopted across Chrome, Firefox, and (much, much later) Safari. These headers give the server contextual information about how a request was triggered, like "the user started this top level navigation by typing the URL in the address bar" and something like that... this is doable because your browser always knows whether a navigation came from a link click, from an embedded iframe, from a script fetch, or from opening a new tab, etc...

Officially they were introduced for security check, trying to:

- Reduce CSRF and XS-Leaks attack surface by telling the server whether the request is cross-site, same-origin, or user-initiated, many attacks become easier to block.

- Enable server side enforcement based on navigation context a server can reject cross-site navigations to protected pages or block dangerous embedding.

- Expose subtle inconsistencies in headless automation these headers come from the browser’s internal navigation stack. Recreating them manually is difficult, and automation frameworks often leak inconsistencies.

In the screenshot above we've:

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-Site: none

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Here’s what each one means.

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document describes the intended destination of the request. document is what you expect when the browser loads a top-level HTML page. Here too, headless (or poorly-configured/stupid bots) often send "empty", "script", or omit the header entirely, which is an immediate red flag.

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate indicates how the request was triggered. navigate is the mode for real page navigations: typing a URL, clicking a link, browser redirects. Automation tools often send "no-cors" or "cors" even when they pretend to "load a page".

Sec-Fetch-Site: none is one of the most interesting pieces. none means the request wasn’t initiated from another webpage. Typical cases include:

- typing the URL manually

- opening a new tab

- a bookmark

- a redirect initiated by the browser itself

This is coherent for a first-page load. Many headless bots incorrectly say cross-site even on initial navigations...

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1 header is sent only when a real user gesture triggered the navigation (like clicking on something). It is not sent for fetch API calls, iframes, images, preloads, or passive navigations. This makes it one of the most reliable "human intent" signals in HTTP traffic. Bots often add it manually without reproducing the renderer state that would normally produce it, resulting in contradicting metadata.

Why headless browsers expose identity inconsistencies?

UA-CH and Sec-Fetch come from different parts of the "browser pipeline" and, under normal conditions, are internally consistent. A real browser has a rendering engine, a navigation context, a visible top level document, a frame tree, a full UA-CH pipeline, permissions policies and a dozen of other moving pieces that all agree on "where the request comes from" and "who the client claims to be".

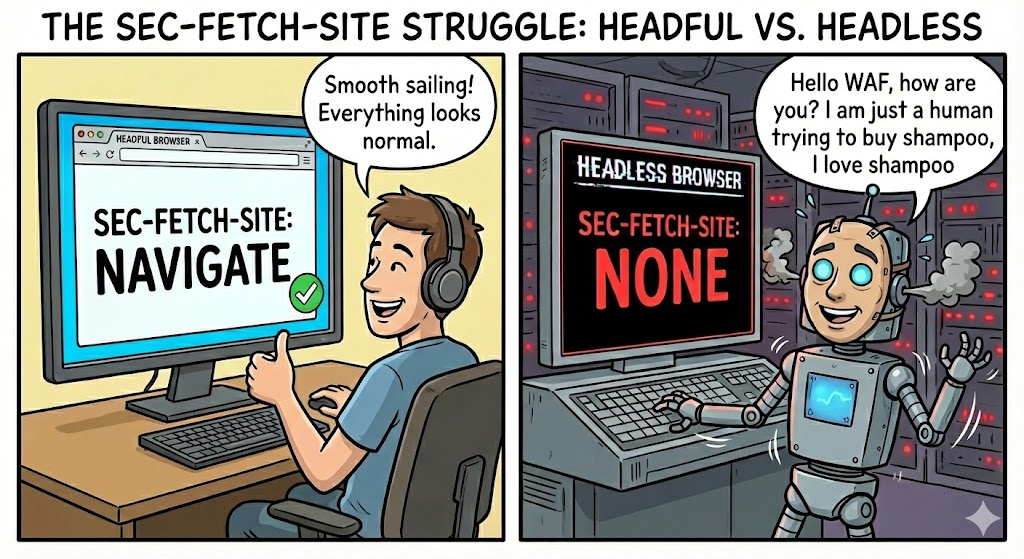

Despite what you may think, headless Chromium is way different from a "real" browser used by a human. When the browser runs without a graphical environment, several subsystems are disabled or partially stubbed. The identity layer becomes thinner, and some components that normally collaborate to generate Fetch Metadata and UA Client Hints simply do not run. This is exactly why you see missing Client Hints, or values that do not match the declared User Agent, or sec-fetch-site set to none even when the request originates from a navigation path that should produce same-origin or same-site.

This is not speculation. The Chromium issue tracker show users reporting that headless Chrome fails to send Client Hints even though the JS environment inside the page can read them without any problems. One example is a bug report where developers noticed that in headless mode the CH headers are not present while the browser still exposes the correct data through JavaScript.

There are also multiple community discussions from automation developers who discovered that headless Chrome behaves differently at the network layer. Some noticed that resources load in different order compared to headful Chrome, or that certain fetches fail only in headless mode. A Reddit thread even highlights that "headless Chrome doesn’t load content the same way normal Chrome does", which is another indirect symptom of the reduced identity and navigation context used in headless environments.

Combine all this and you get a very predictable outcome: automation frameworks like Selenium, Puppeteer or Playwright, when running in true headless mode, generate requests that contain identity gaps. The User-Agent may claim "Chrome 142", but the Client Hints announce a different major version, or they are missing entirely. The Fetch Metadata headers may describe a navigation that does not exist, or they may fall back to defaults that a real browser never produces in the same situation.

These inconsistencies show how complex browser identity has become and how heavily it depends on the presence of a real rendering pipeline. For us as defenders that creates an excellent opportunity because they're hard for bot developers to fake.

Real inconsistencies between headless and real browsers

Below are the inconsistencies that appear repeatedly in the wild on our Web Application & API Protection service logs.

Sec-Fetch-Site "none" during an internal navigation

One of the most common inconsistencies is seeing Sec-Fetch-Site: none on requests that are clearly part of an internal site navigation. A real browser only sends "none" when the request originates from an address-bar navigation, a bookmark, an external protocol handler, or something happening outside the page context. In headless automation you often see none on XMLHttpRequest calls, form submissions, or follow-up navigations, simply because the browser lacks a proper top-level browsing context.

User-Agent and Client Hints disagreeing on platform

Another clear inconsistency is when the UA claims "Linux" or "macOS" but the Client Hints say "Windows", or vice versa. We see a lot of requests with:

UA: Chrome/141 Linux x86_64

CH-UA-Platform: "Windows"

This cannot happen in a real graphical Chrome session. When Chromium runs headless or through automation layers, the UA can be freely spoofed, but the CH pipeline often falls back to defaults or reports the host OS instead of the spoofed one. That is why CH-UA-Platform exposes the truth even when the UA string is forged. This mismatch is one of the strongest detection signals because it is extremely difficult for bots to synchronize the whole identity stack consistently.

Client Hints present but implausible browser versions

This is a tricky one, we've a lot of requests where the UA claims Chrome/140 or Chrome/141.0.0.0, but the Client Hints report completely different versions (sometimes older, sometimes fixed values like v="24"). Real Chrome aligns the UA major version with Sec-CH-UA in a predictable way. Automation frameworks that override the UA or run patched builds often leave the CH values untouched. The result is something like:

UA: Chrome/140

CH-UA: "Chromium";v="100", "Google Chrome";v="100"

This is not a pattern you ever see in legitimate user traffic. It is, however, extremely common in scraping frameworks and patched Chromium builds.

Missing Client Hints on browsers that should send them

A pattern we've seen many times: requests claiming Chrome 140+, 141+, 142+ but with no Client Hints at all. This is suspicious because Chrome has shipped UA-CH by default for a long time and always sends hints (browser brand, major version, platform, mobile flag, etc...) unless explicitly disabled. Headless Chrome and automation wrappers frequently fail to initialize the Client Hints subsystem or run in contexts where CH delegation does not activate.

Sec-Fetch-Mode set to navigate on requests that are not navigations

Many of the request blocked by our WAAP include XHR or form POST requests marked as sec-fetch-mode: navigate. This does not happen in real sessions. A normal browser only sets navigate for top-level or iframe navigations that load a document. When automation scripts programmatically calls .click(), .goto(), or patched navigation flows, the fetch metadata env is not fully engaged, so the browser ends up misclassifying requests. These mismatches are very visible and cannot be easily controlled by the bad bot developer.

Implausible platform claim: UA says desktop, CH says Android

One recurring inconsistency is a desktop-looking UA (Linux x86 or Windows NT 10) combined with Sec-CH-UA-Platform: "Android". A real Chrome instance cannot run in this configuration. Bots running inside Android emulators, nested virtual machines, or using patched Chromium forks often misreport the platform through CH because the automation layer exposes an Android user environment while the UA was manually spoofed to look like desktop. This mismatch is a definitive signal of non-human traffic.

Sec-Fetch-Dest always set to document even for XHR or form POST

Some of our WAAP logs show sec-fetch-dest: document on XHR requests or asynchronous POST requests. A real browser uses empty for XHR/fetch requests and reserves document for page loads. This is another symptom of navigation metadata not being correctly populated in headless mode. The destination is guessed generically rather than derived from an actual renderer.

Requests that should include Sec-Fetch-User: ?1 but don’t

The Sec-Fetch-User header appears only when a user gesture (click, tap) triggered a navigation. This is a classic automation signature: programmatic navigations (page.goto(), browser.navigateTo()) simulate the effect of clicking, but not the user interaction itself. Real users generate more ?1 tokens than bots.

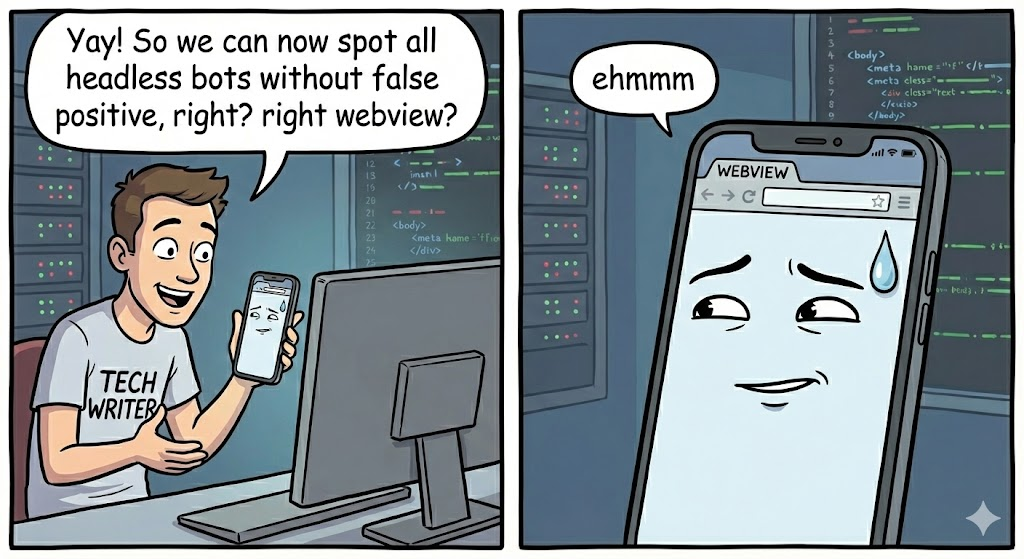

Yay! So we can now spot a lot of headless without false positive, right?

ehm... ok, we've a problem called webview and maybe it is worth remembering what a WebView actually is. On Android, android.webkit.WebView is not a full standalone browser but an embeddable rendering component that apps use to display web content inside their own UI. On iOS the equivalent is WKWebView. Both reuse the underlying rendering engine, but the navigation stack, header generation, UA composition and event pipeline are controlled by the host app, not by a real browser.

From the Client Hints perspective, this is a crap! Android WebView only recently gained proper support for User-Agent Client Hints. Google explicitly states that WebView supports UA-CH starting from version 116, but only when the application uses the default system user agent. If the app overrides the UA string, Client Hints may not be sent at all (https://android-developers.googleblog.com/2024/12/user-agent-reduction-on-android-webview.html).

MDN’s compatibility tables confirm that UA-CH support has been partial or missing for WebView and iOS WKWebView for a long time (https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Client_hints#browser_compatibility).

Chromium developers also discussed the issue publicly, explaining how UA-CH had been disabled in WebView until their semantics and interaction with app-level UA overrides could be clarified (https://bugs.chromium.org/p/chromium/issues/detail?id=1134637).

If your detection rule says "modern Chrome without Client Hints looks like a bot", WebViews will trigger that rule constantly. Missing Sec-CH-UA, missing Sec-CH-UA-Platform, missing Sec-CH-UA-Mobile, and generally zero high-entropy hints are absolutely normal for WebViews. From a server perspective, that looks identical to a bot that spoofed a Chrome 142 UA without sending CH.

User-Agent Reduction complicates things even more. Android’s WebView now applies the same reduction strategy as Chrome: the UA string is frozen to a generic OS and device ("Linux; Android 10; K"), and minor versions are collapsed to 0.0.0. The same Google announcement describes this clearly: https://android-developers.googleblog.com/2024/12/user-agent-reduction-on-android-webview.html

This means a UA like Chrome/142.0.0.0 is perfectly legitimate for WebView. If your rule thinks this is suspicious or "bot-like", you will get completely normal traffic misclassified as automation, and you don't want it... belive me, you don't 😄

Fetch Metadata (the Sec-Fetch-* headers) is another area full of "edge cases". A WebView app often calls loadUrl() directly or wires its own custom navigation delegate. These code paths bypass several browser-layer checks that normally populate Sec-Fetch-Site, Sec-Fetch-Mode, Sec-Fetch-Dest and Sec-Fetch-User. The result is that legitimate WebView traffic might:

- omit all Sec-Fetch-* headers

- always send

Sec-Fetch-Site: none - miss

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1even after a valid user gesture

From a WAF point of view, this is indistinguishable from a headless browser (unfortunately).

The X-Requested-With header is another shitty ambiguous header. Android WebView used to send it on every request, with the value being the app’s package name (I know... it doesn't make any sense, totally). This was meant as a sort of "WebView identification mechanism" but became a privacy issue (oh yes? really?). Many app developers now strip it or alter it... Google is gradually making it optional for privacy reasons, documented here: https://developer.android.com/privacy-and-security/changes/requested-with

Because of this, relying on X-Requested-With to flag WebViews or distinguish real clients from bots is unreliable: some apps send it, others remove it, others change it inconsistently.

So, all this words just to say: are you a bad bot developer? Make your bad bot look exactly like a webview and nobody will block you 😄

Conclusion

This post shows that modern bot detection is no longer about finding a single "bad signal". The User-Agent string alone is useless in this way, JavaScript execution is not a proof of a real user anymore, and even Client Hints, if analysed one by one, are not enough. What really matters today is the coherence of the whole browser identity.

Client Hints and Fetch Metadata were introduced mainly for privacy and performance reasons, but in practice they describe a browser and how it behaves in a very structured way. This is an important lesson for anyone building detection rules: using a single signal, like "headless equals bot" or "User-Agent start with Mozilla, everything fine!", creates many false positives and, moreover, it's a completely waste of CPU especially with WebViews.

UA, Client Hints, JavaScript-exposed entropy, and sec-fetch metadata together give you a single identity map and you can easily check if this map is coherent and decide if you want an incoherent browser on you websites.

For large e-commerce platforms under automated abuse, this difference is critical. Blocking at the wrong level hurts real users and damages conversion rates. Understanding how browsers really identify themselves, and how automation fails to fully reproduce this identity, is the key to protecting high-value workflows without destroying the user experience.

If you want to know more about how we do it, feel free to contact me.