In some ways, the humble door handles we use to open our vehicles haven’t changed much in over five decades. In others, today’s modern handles represent a leap forward in technology.

In the formative years of automotive design, vehicle door handles were nearly identical to those being used in people’s homes and workplaces. A simple bar or pin was attached to a rotating handle to latch or release the door. These grew into the twist handles most often associated with vehicles made into the 1950s.

From there, door handles became varied, with a “flap” style, pull-up or pull out style, push-button, and other variations. All of these worked on the same general principle. Unlike the earlier handles, these were no longer always physically in-line with the latch that held the door shut. Instead, rods or cables would transfer the human hand motion of opening the door to the latch itself. This change happened sometime in the 1950s, but which vehicle used it first is unclear.

The style of the exterior door handle was usually dictated by the style of the vehicle and what was popular at the time. In the 1960s and 70s, for example, the push-button style of handle was popular. The user simply gripped a handle to pull the door open and used a thumb to press a button to unlatch the door. The 2025 Mercedes-Benz G-Wagen uses this type of handle as one of many nostalgic throwbacks in its design.

Around the same time, pull-up style handles also became popular on more affordable vehicles. These designs were prized for their simplicity, providing both a functional grip and a direct mechanism to activate the latch. Today, these handles are more often seen on luxury sports cars, having come full circle in design prestige.

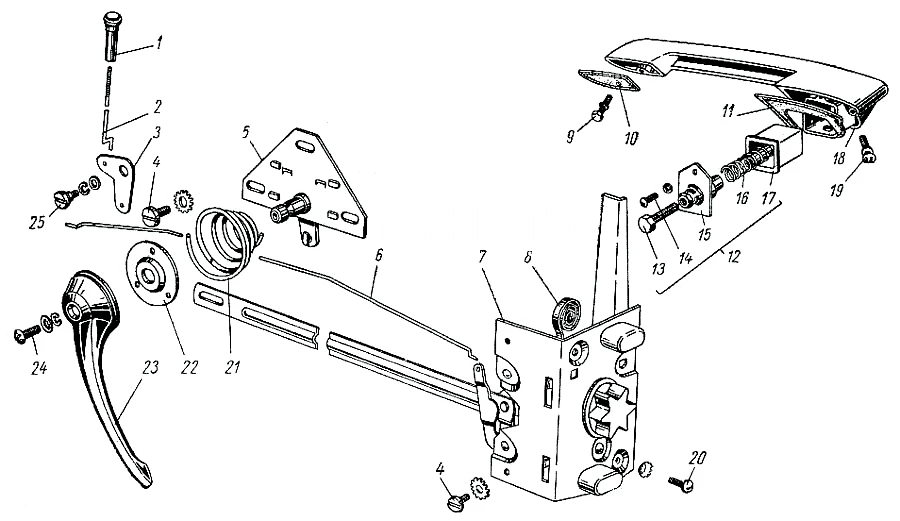

This OEM repair illustration from Chevrolet shows the pull-latch and twist-handle interior/exterior on a 1962 model

Chevrolet

The most enduring type of door handle, however, and the one with the longest use in automotive production, is the pull out style. These are similar to the pull-up, but pull away from the vehicle rather than upwards. These are simple, intuitive, and relatively easy to manufacture. Most of today’s popular “flush” handles are pull-out styles once revealed.

The latest handle type, the flush handle, comes in two basic varieties. Their primary difference lies in how they extend outward from the vehicle. Some use an actuator to push the handle away from the car and pull it back in. Others are spring-loaded, using the actuator only to hold the handle in. This latter type addresses the safety concerns of power outages disabling car door access. They work in a way similar to the air brakes on a heavy-duty vehicle: as long as there’s power to keep the actuator active, the handle stays in. If power is lost, the springs in the handle automatically release it.

Inside the door, the changes in door handle design haven’t been as dramatic. Most door handles today still physically pull a rod or (more often) cable that manipulates the latch. Even modern electronically actuated door latches have a physical backup using this simple mechanism in case the vehicle loses power. The linkage used in this part of the door handle/latch connection hasn’t changed much since the 1970s.

What has changed significantly is the position of the latch itself. Once door handles were no longer required to be in line with the latch, that freed engineers and designers from rigid placement and allowed experimentation in both how the handles looked and how they were used; as well as in where the latch was located. This greatly improved both design aesthetics and safety.

Today, most car doors have a striker or lock to which the door latch attaches when the door is closed. These are usually U-shaped and attach directly to the body frame of the vehicle.

Because the door handle and latch are no longer required to be in line with one another, strikers/locks are positioned for safety rather than convenience. They are usually lower down than the actual door handle, at the door’s mid-point by mass (rather than shape) – generally geometrically in line or near to in line with the center point of the door hinges opposite. Both the latch and striker combination and the door’s hinges are designed to remain intact even after significant body buckling.

As crash testing improved, so did our understanding of safety. During Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) tests, for example, if a car’s door opens at any point during a crash test, the vehicle’s score is automatically downgraded to a low score of “Poor.” Open doors mean the potential for much more significant injuries. Preventing this requires precise engineering of both the latch and hinge.

When pushed, the combination latch handle on today's Lexus vehicles electronically releases the latch – when pulled, as shown, it acts as a physical handle, pulling a cable to manually unlatch

Aaron Turpen / New Atlas

Returning attention to the door handles we interact with to open the car’s door, there have been numerous design changes in the past 50 years or so. And not only for aesthetic reasons.

Door handles can be a significant drag for aerodynamics. So smoothing, tucking in, and other changes have happened over the years to address that. Until recently, most of those changes involved either streamlining the handle itself with a sharper profile and thinner protrusion from the vehicle’s body or moving the handle to a more aero-favorable position. The C8 Corvette, for example, has its exterior handles tucked in behind an aerodynamic tunnel in the bodywork. Many vehicles have used this tactic in the past few decades.

More recently, there's been a trend of “suck-in” handles that are flush with the body. As noted earlier, flush handles come in two basic varieties. All of them have the same goal: streamlining aerodynamics. Hopefully without compromising usability or aesthetics. Aesthetically, the two varieties are traditional, bulky grip handles that attach to either side of the handhold and the flap-out style that connect on only one side. Mercedes-Benz, Tesla, and others use the former type while Kia, Rivian, and others use the latter.

While physical handle mechanisms have changed little, how we interact with them has evolved. Whether you’re using a smartphone, chipped card, keyless fob, or even a voice command to unlock the car, the final act of opening the door often still involves a mechanism that hasn’t changed much in half a century.

This blend of old and new is emblematic of automotive design. While we often focus on what’s novel, the enduring functionality of elements like the door handle reminds us that innovation often builds on what already works.

Like the humble door handle.