Last week, I pointed my domain to a new server. Changed the A record, waited... nothing. The old site kept showing up. I cleared my browser cache. Still nothing. Restarted my computer. Nothing.

Three hours later, I learned about DNS propagation and TTL. That rabbit hole led me to actually understand how DNS works. Not just "it translates domains to IPs" - but the whole system.

Here's what I learned.

At its core, DNS is simple: it translates domain names into IP addresses. You type example.com, DNS returns 93.184.216.34, and your browser connects to that IP. Without DNS, you'd need to memorize IP addresses for every website. Nobody wants that.

But the how is where it gets interesting.

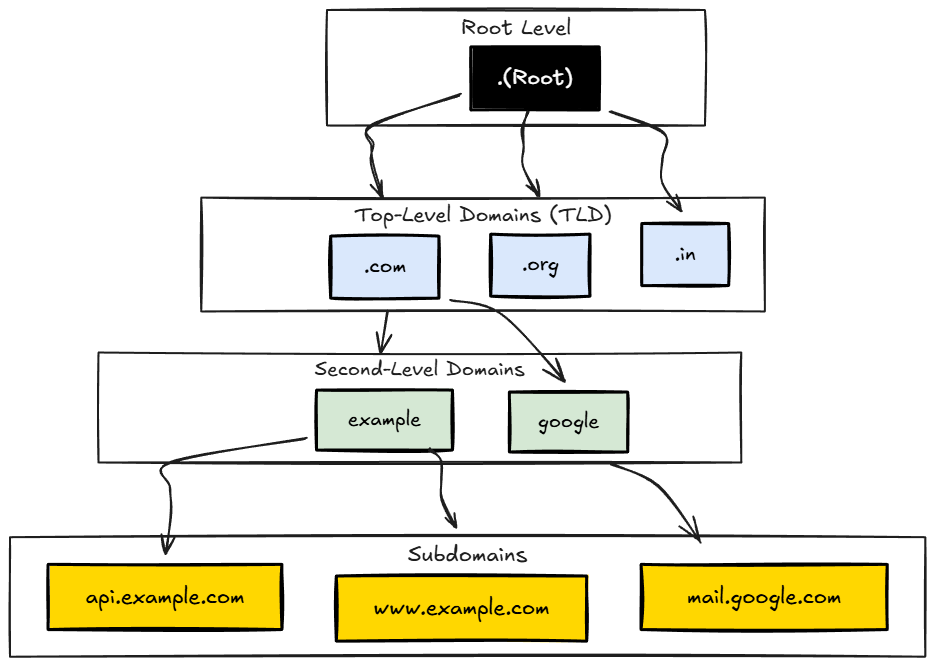

DNS Hierarchy

Here's the mental model that finally made DNS click for me: it's organized like a chain of referrals. Each level knows about the level below it, and nobody knows everything.

Root (.)

Every DNS lookup starts here. I didn't even know root servers existed until I had to debug my propagation issue. There are 13 root server clusters worldwide, operated by organizations like Verisign, ICANN, and NASA. Root servers don't know where example.com is - but they know where to find the .com TLD servers. They're the starting point of the referral chain.

TLD (Top Level Domain)

You know this part - the last bit of a domain: .com, .org, .in, .io. TLD servers know all domains registered under them. The .com TLD knows where to find example.com, google.com, and every other .com domain.

Common TLDs:

.com- Commercial (anyone can register).org- Organizations.net- Network services.io- British Indian Ocean Territory (popular with tech).dev- Developers (requires HTTPS).gov- US Government only.edu- Educational institutions

Domain

The name you actually buy: example, google, github. Combined with TLD, you get example.com. This is what you purchase from registrars like Namecheap, GoDaddy, or Cloudflare. I use Cloudflare for my domains - the DNS management is clean and free. (Once you understand DNS, you might want to check out my guide on deploying Django REST Framework to production - that's where you'll actually use this knowledge.)

Subdomain

Anything before the domain: api.example.com, mail.example.com, staging.example.com. The cool part? You create these yourself through DNS records. No additional purchase needed. If you own example.com, you can create unlimited subdomains for free.

DNS Records

When I first opened my domain's DNS panel, I saw a bunch of record types I didn't understand. A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, TXT... it looked intimidating. But once you know what each one does, it's actually straightforward.

A Record

This is the one you'll use most. Maps a domain to an IPv4 address. When I moved my site to a new server, this is what I changed.

example.com A 93.184.216.34

When someone requests example.com, DNS returns 93.184.216.34.

AAAA Record

Same thing, but for IPv6 addresses. The weird name? Four A's because IPv6 addresses are four times longer than IPv4. I haven't had to set one of these up myself yet.

example.com AAAA 2606:2800:220:1:248:1893:25c8:1946

CNAME (Canonical Name)

This one's clever. Instead of pointing to an IP, it points to another domain. It says "go ask this other domain instead."

www.example.com CNAME example.com

blog.example.com CNAME example.ghost.io

Super useful when you use third-party services. I use this to point subdomains to hosted services - your blog can point to Ghost, your docs to GitBook, without managing their IPs yourself.

MX (Mail Exchange)

Ever wondered how [[email protected]](https://www.bhusalmanish.com.np/cdn-cgi/l/email-protection) knows where to go? MX records. They specify where to deliver emails for your domain. The priority number matters - lower numbers are tried first.

example.com MX 10 mail1.example.com

example.com MX 20 mail2.example.com

When someone emails [[email protected]](https://www.bhusalmanish.com.np/cdn-cgi/l/email-protection), mail servers check the MX record to find where to deliver. If mail1 (priority 10) is down, it tries mail2 (priority 20).

TXT Record

This one seems random at first - it just stores text. But it's used for some important stuff.

example.com TXT "v=spf1 include:_spf.google.com ~all"

example.com TXT "google-site-verification=abc123xyz"

I've used TXT records for:

- Domain verification - Google, Stripe, AWS ask you to add a TXT record to prove you own the domain

- SPF - Specifies which servers can send email on your behalf (prevents spoofing)

- DKIM - Email authentication using cryptographic signatures

- DMARC - Policy for handling failed SPF/DKIM checks

TTL (Time To Live)

This is what got me. Remember my three hours of confusion? The TTL on my old A record was 3600 seconds. That's one hour. Every resolver that had cached my old IP would hold onto it for up to an hour before checking again.

TTL tells resolvers how long to cache a DNS result.

example.com A 93.184.216.34 TTL=3600

This means: "Cache this answer for 3600 seconds (1 hour). Don't ask again until then."

Common TTL values:

- 300 (5 min) - Frequent changes, quick failover needed

- 3600 (1 hour) - Normal websites

- 86400 (1 day) - Rarely changes

The Trade-off

Low TTL = Faster updates, but more DNS queries (slightly slower first load).

High TTL = Fewer DNS queries (better performance), but slower propagation when you change records.

Pro tip I learned the hard way: if you're planning to migrate servers, lower your TTL to 300 a few days before. After migration, old cached records expire in 5 minutes instead of hours. Wish I'd known this before my migration.

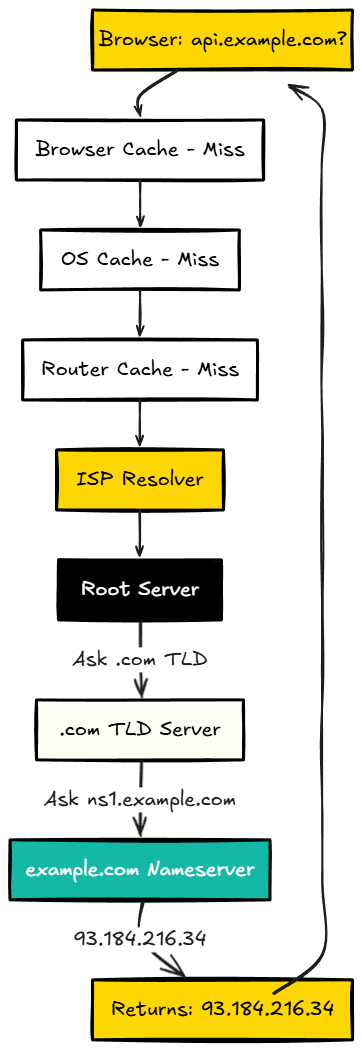

DNS Resolution Process

Once I traced through this whole process, everything clicked. Here's what actually happens when you type api.example.com in your browser:

Step 1: Browser cache

"Do I have api.example.com cached?" → No

Step 2: OS DNS cache

"Do I have it?" → No

Step 3: Router cache

"Do I have it?" → No

Step 4: ISP's DNS Resolver

"Do I have it?" → No, let me find out...

Step 5: Ask Root Server

Resolver: "Where is api.example.com?"

Root: "I don't know, but .com TLD is at 192.5.6.30"

Step 6: Ask .com TLD Server

Resolver: "Where is api.example.com?"

TLD: "I don't know, but example.com's nameserver is at ns1.example.com"

Step 7: Ask example.com's Nameserver

Resolver: "Where is api.example.com?"

NS: "It's at 93.184.216.34"

Step 8: Response flows back

Resolver caches it (based on TTL)

Returns 93.184.216.34 to your browser

Step 9: Browser connects to 93.184.216.34

Visual representation:

Each intermediate resolver caches the result based on TTL. Subsequent requests from the same network skip most of this because the resolver already knows the answer. That's why the second visit to a site is faster than the first.

What is a Resolver?

I used to confuse resolvers and nameservers. They sound similar, but they do different jobs.

A resolver is a DNS server that does the hard work of finding IP addresses for you. It handles the recursive lookup through Root → TLD → Authoritative nameservers.

Your device asks a resolver: "What's the IP of example.com?" The resolver does all the work and returns: "It's 93.184.216.34"

Common public resolvers:

8.8.8.8- Google Public DNS1.1.1.1- Cloudflare (fastest, privacy-focused)208.67.222.222- OpenDNS (Cisco)9.9.9.9- Quad9 (security-focused, blocks malware)

You can change which resolver you use in your network settings. I switched to 1.1.1.1 on my machines - it's noticeably faster than my ISP's default resolver.

What is a Nameserver?

A nameserver is the source of truth. It actually holds the DNS records for a domain. When you register a domain, you point it to nameservers that store your A records, CNAME records, MX records, etc.

The difference between resolvers and nameservers:

- Resolver - Finds answers by asking other servers (the messenger)

- Nameserver - Holds the actual DNS records (the source of truth)

When you buy a domain from Namecheap or GoDaddy, they give you default nameservers like:

ns1.namecheap.com

ns2.namecheap.com

You can change these to use Cloudflare, AWS Route 53, or your own nameservers:

# Cloudflare nameservers

ns1.cloudflare.com

ns2.cloudflare.com

# AWS Route 53 (example)

ns-1234.awsdns-56.org

ns-789.awsdns-12.co.uk

Why bother changing nameservers? Different providers offer different features. I moved my domains to Cloudflare because they give you free DDoS protection, a CDN, and the dashboard is just nicer to use. Route 53 makes sense if you're already deep in AWS.

Authoritative vs Recursive

Authoritative nameserver - Has the final answer for a domain. When asked "Where is example.com?", it responds with the actual IP because it holds the records.

Recursive resolver - Doesn't hold records, but finds answers by asking authoritative servers. Your ISP's DNS server and 8.8.8.8 are recursive resolvers.

View DNS Cache

These commands saved me during my debugging session. When you need to see what's actually cached:

In Browser

# Chrome

chrome://net-internals/#dns

# Firefox

about:networking#dns

# Edge

edge://net-internals/#dns

These show all cached domains with their IPs and remaining TTL.

On Your Computer

# Windows (Command Prompt)

ipconfig /displaydns

# Mac

sudo dscacheutil -cachedump

# Linux

# Most distros use systemd-resolved

resolvectl statistics

Query a Domain

# Using nslookup (Windows/Mac/Linux)

nslookup example.com

# Using dig (Mac/Linux - more detailed)

dig example.com

# Query specific record type

dig example.com MX

dig example.com TXT

# Query using a specific resolver

dig @8.8.8.8 example.com

dig @1.1.1.1 example.com

Clear DNS Cache

Browser

Go to chrome://net-internals/#dns and click "Clear host cache".

Operating System

# Windows

ipconfig /flushdns

# Mac

sudo dscacheutil -flushcache; sudo killall -HUP mDNSResponder

# Linux (systemd)

sudo systemd-resolve --flush-caches

This is what I should've done first. Flushing the cache forces your system to fetch fresh DNS records instead of using stale cached ones.

Why DNS Matters for System Design

Here's where DNS gets interesting beyond just "hosting a website." If you're designing systems at scale, DNS becomes a tool, not just a lookup service.

Load Distribution

DNS can return different IPs for the same domain. Each request might get a different server. This is called DNS round-robin load balancing.

example.com A 93.184.216.34

example.com A 93.184.216.35

example.com A 93.184.216.36

Failover

If one server dies, DNS can stop returning its IP. Health checks detect the failure, DNS record is updated, traffic flows to healthy servers.

Geographic Routing

Return IPs of servers closest to the user. A user in Europe gets European server IPs, a user in Asia gets Asian server IPs. This is called GeoDNS or latency-based routing.

Caching Trade-offs

DNS caching reduces lookup time and load on DNS servers. But it makes instant updates impossible. If you change an IP and TTL is 24 hours, some users will hit the old IP for up to 24 hours.

Quick Reference

┌─────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Term │ What it does │

├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Root │ Top of DNS tree, knows TLD locations │

│ TLD │ .com, .org, .io - knows domains under │

│ Domain │ What you buy (example, google) │

│ Subdomain │ What you create free (api, www, mail) │

├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ A Record │ Domain → IPv4 address │

│ AAAA Record │ Domain → IPv6 address │

│ CNAME │ Domain → Another domain (alias) │

│ MX │ Where to send email │

│ TXT │ Verification, SPF, DKIM, DMARC │

├─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ TTL │ Cache duration in seconds │

│ Resolver │ Server that finds IPs for you │

└─────────────┴────────────────────────────────────────┘

DNS broke my site for three hours. But now I actually understand it - not just what it does, but how it works. Next time something doesn't propagate, I'll know exactly where to look.

What's something you use every day but never really understood until it broke?

Manish Bhusal

Software Developer from Nepal. 3x Hackathon Winner. Building digital products and learning in public.