Vibe coding is the creation of large quantities of highly complex AI-generated code, often with the intention that the code will not be read by humans. It has cast quite a spell on the tech industry. Executives push lay-offs claiming AI can handle the work. Managers pressure employees to meet quotas of how much of their code must be AI-generated or risk poor performance reviews. Software developers worry that everyone around them is a “10x developer” and that they’ve fallen behind. College students wonder if it is worth studying computer science now that AI has automated coding. People of all career stages hesitate to invest in their own career development. Won’t AI be able to do their jobs for them anyway a year from now? What is the point?

I work at an AI company, and we use AI every day. AI is useful! However, we approach vibe coding with caution and have seen that much can go wrong.

The results of vibe coding have been far from what early enthusiasts promised. Well-known software developer Armin Ronacher powerfully described some of the issues with AI coding agents. “When [I first got] hooked on Claude, I did not sleep. I spent two months excessively prompting the thing and wasting tokens. I ended up building and building and creating a ton of tools I did not end up using much… Quite a few of the tools I built I felt really great about, just to realize that I did not actually use them or they did not end up working as I thought they would.”

Armin titled his post “agent psychosis”. The term “psychosis” is a strong label. What is it about this technology which could be trapping such productive and experienced developers? The reason may be similar to the addictive qualities of gambling, a sinister under-current of the normally positive state of flow.

Not all Focus is Flow

When coding or doing other creative work, many of us experience a state of flow: full absorption and energized focus. This concept was first formalized by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in the 1970s. In his 1990 best-selling book, he described flow as “a sense that one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing.”

There are activities that can produce feelings of absorption and engaged focus that don’t meet this positive definition of flow. Consider gambling. A key aspect of flow is that the challenge faced be reasonably matched to the person’s skills. “Roulette players develop elaborate systems to predict the turn of the wheel,”Csikszentmihalyi writes of how gamblers often believe their skills are playing a significant role, even in games governed entirely by chance.

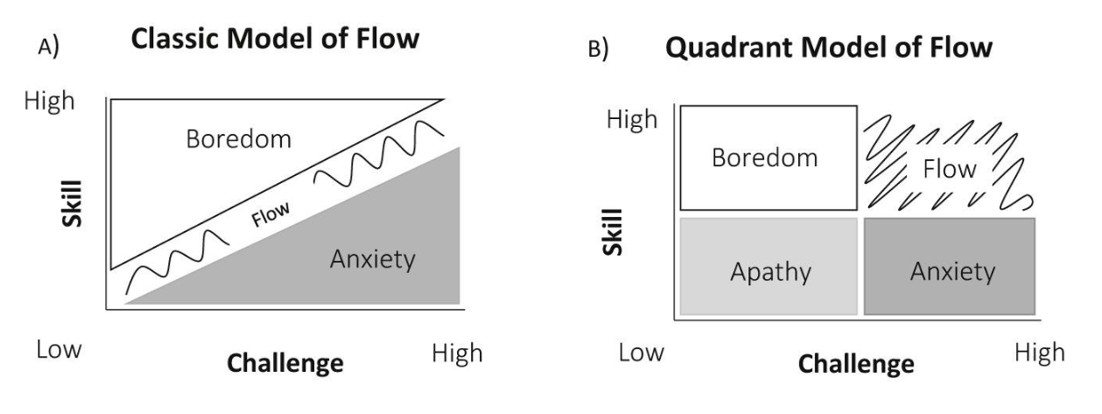

Csikszentmihalyi emphasized the importance of skill and challenge being appropriately matched. He later highlighted that optimal flow occurs with high skill and high challenge. Figure adopted from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8943660/

Another key aspect of this kind of flow is that the activity should provide “clear clues as to how well one is performing.” The makers of modern slot machines have gone to great lengths to do the opposite, creating the outcome of a Loss Disguised as a Win (LDW).

On a traditional slot machine, you either win or lose. In contrast, multiline slot machines have 20 rows going at once and reward partial “credits” that create a false sense of winning even as you lose. For example, you can gamble 20 cents and receive a 15 cent “credit”. This is actually a 5 cent loss, yet the slot machine plays celebratory noises that trigger a positive dopamine reaction. Research shows these games induce a similar physiological reaction to an actual win and players are more likely to enter a highly absorbed, flow-like state.

This slot machine allows 4 lines to be played at once; some allow up to 20 lines. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Researchers on gambling addiction have coined the term “dark flow” to describe this insidious variation on true flow. In a 2014 interview, Csikszentmihalyi defined the idea of “junk flow”: “Junk flow is when you are actually becoming addicted to a superficial experience that may be flow at the beginning, but after a while becomes something that you become addicted to instead of something that makes you grow. The problem is that it’s much easier to find pleasure or enjoyment in things that are not growth-producing but are attractive and seductive.”

The concepts of “junk flow” or “dark flow” align with many people’s experience of vibe coding. The results can be disastrous.

Parallels between Vibe Coding and Gambling

Look back at Armin’s experience again: “Quite a few of the tools I built I felt really great about, just to realize that I did not actually use them or they did not end up working as I thought they would.” This sounds like the Loss Disguised as a Win concept from gambling addiction. Consider the hundreds of lines of code, all the apps being created: some of these are genuinely useful, but much of this code is too complex to maintain or modify in the future, and it often contains hidden bugs.

One thing many of us love about computer programming is our experiences of flow. On the surface, vibe coding can seem to induce a similar flow. However, it often violates the same characteristics of flow that fail with gambling:

- Vibe coding does not provide clear clues of how well one is performing (and even provides misleading losses disguised as wins).

- The match between challenge level and skill level is murky.

- It provides a false sense of control in which people think they are influencing outcomes more than they are.

With vibe coding, people often report not realizing until hours, weeks, or even months later whether the code produced is any good. They find new bugs or they can’t make simple modifications; the program crashes in unexpected ways. Moreover, the signs of how hard the AI coding agent is working and the quantities of code produced often seem like short-term indicators of productivity. These can trigger the same feelings as the celebratory noises from the multiline slot machine.

Vibe coding provides a misleading feeling of agency. The coder specifies what they want to build and is often presented with choices from the LLM on how to proceed. However, those options are quite different than the architectural choices that a programmer would make on their own, directing them down paths they wouldn’t otherwise take.

Both slot machines and LLMs are explicitly engineered to maximize your psychological reaction. For slot machines, the makers want to maximize how long you play and how much you gamble. LLMs are fine-tuned to give answers that humans like, encouraging sycophancy and that they will keep coming back. As I wrote in a previous blog post and academic paper, AI can be too good at optimizing metrics, often leading to harmful outcomes in the process.

Unreliable narrators

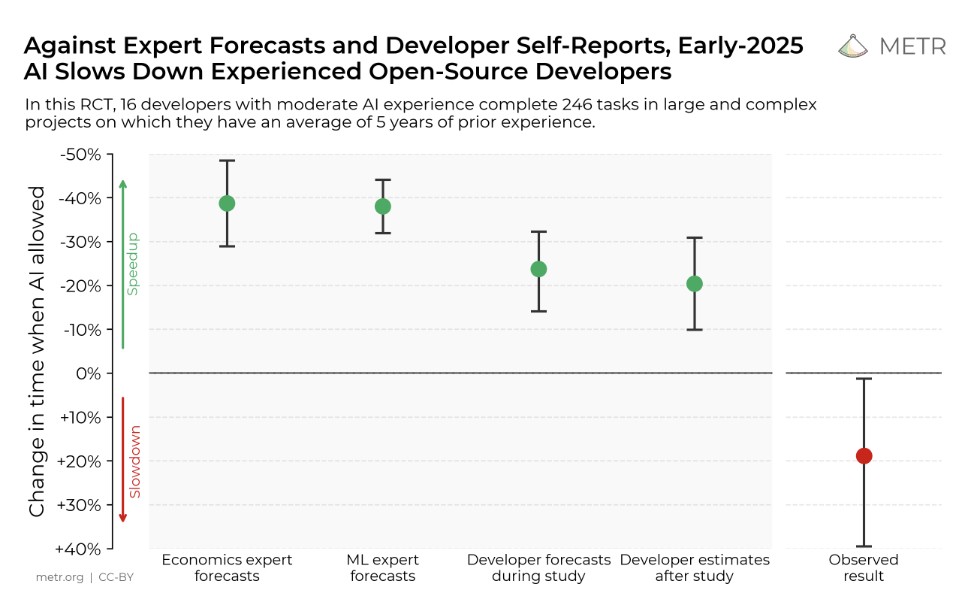

With “junk” (or “dark”) flow we lose our ability to accurately assess our productivity levels and the quality of our work. A study from METR found that when developers used AI tools, they estimated that they were working 20% faster, yet in reality they worked 19% slower. That is nearly a 40% difference between perceived and actual times!

Developers thought that AI was helping them speed up, but it was actually slowing them down. Source: https://metr.org/blog/2025-07-10-early-2025-ai-experienced-os-dev-study/

It is difficult to evaluate claims from those who enthuse about their productivity with vibe coding. While prior expertise in software engineering and knowledge on providing effective context are useful, their impact on vibe coding results is non-linear and opaque.

I found myself unable to read the latest 2 posts of a blog by a leading AI researcher that I have subscribed to (and previously enjoyed) for 10 years. I happened to skip ahead to a subsection of one of the posts, where the author revealed that he had used AI to generate these latest 2 posts. He wrote that he was producing writing of the same quality, only much faster than before. The writer is an intelligent and highly accomplished person whom I respect, yet he seemed unaware that these posts read quite differently than his earlier work. For me at least, they were less readable than his previous articles.

Social media is full of accounts saying how much more they are accomplishing with AI. People may genuinely believe what they are saying, yet individuals are terrible judges of their own productivity.

Failed Predictions

It is worth experimenting with AI coding agents to see what they can do, but don’t abandon the development of your current skillset. Part of the appeal of vibe coding is claimed extrapolation about how effective it will be 6 or 12 months from now. These predictions are pure guesswork, often based more on hope than reality.

Renowned AI researcher Geoffrey Hinton predicted that AI would replace radiologists by 2021. Google CEO Sundar Pichai and head of AI Jeff Dean predicted that all data scientists would be using neural net architecture search to generate customized architectures for their individual problems by 2023. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei predicted that by late 2025, AI would be writing 90% of all code. There is an entire wikipedia page documenting the failed predictions of Elon Musk on when we would have autonomous vehicles.

Bring a skeptical eye to tech CEO predictions

Should you gamble your career?

We all make mistakes and I am not trying to pick on the people listed above. However, it is important to ask if you want to stop investing in your own skills because of a speculative prediction made by an AI researcher or tech CEO. Consider the case where you don’t grow your software engineering or problem-solving skills, yet the forecasts of AI coding agents being able to handle ever expanding complexity don’t come to pass. Where does this leave you?

While AI tools are genuinely impressive and continue to make improvements, the forecasts from major foundation labs has consistently overstated the pace they will develop. This is nothing new. Tech companies have been overhyping their products for decades.

Human Creativity and Thinking Still Matter

AI coding agents can produce syntactically correct code. However, they don’t produce useful layers of abstraction nor meaningful modularization. They don’t value conciseness or improving organization in a large code base. We have automated coding, but not software engineering.

Similarly, AI can produce grammatically correct, plausible sounding text. However, it does not directly sharpen your ideas. It does not generate the most precise formulations or identify the heart of the matter.

“People who go all in on AI agents now are guaranteeing their obsolescence. If you outsource all your thinking to computers, you stop upskilling, learning, and becoming more competent,” Jeremy Howard shared in his Nvidia Developer interview. AI is a useful tool, but it doesn’t replace core human abilities.

Thank you to Jeremy for feedback on earlier drafts of this essay.